Who said it, when, and why? Part II (of II)

Answers to last week's quiz

Happy Monday. I hope you enjoyed last week’s quiz. More important, however, is that you learned something from the answers provided in the post on Friday, “Who said it, when, and why? Part I.” The time spent sharing these quotes, and their context, seems justified when I receive feedback on the posts. One from a retired Foreign Service Officer included this observation: “Every organizational, conceptual, and doctrinal U.S. deficit in the information space was anticipated in the first postwar decade, it seems, and every time the insights were ignored.” Today is not like yesterday in many respects, but the most important difference is not the technology, despite the conventional wisdom, but the breadth and depth of discussions around the issues. The lack of commitment, leadership, depth of analysis, and consistency shown by both the legislative and executive branches is stunning compared to the depth, frequency, attention, and profile of the executive discussions, planning, and legislative actions in 1945-1952, for example.

Moving on, first here’s a picture from my trail run yesterday with my dog (8.6 miles with about 1100’ of ascent) on a false flat section. It was a beautiful day, naturally. Ok, now let’s get into the answers and context for questions 7-10.

Q7:

The United States Information Service is truly the voice of America and the means of clarifying the opinion of the world concerning us. Its objective is fivefold. To be effective it must (1) explain United States motives; (2) bolster morale and extend hope; (3) give a true picture of American life, methods, and ideals; (4) combat misrepresentation and distortion, and (5) be a ready instrument of psychological warfare when required.

When: 1947, selected by 42% of the respondents (1953 selected by 17%, 1959 enjoyed 42%).

Source: “Preliminary Staff Report of the Smith-Mundt Congressional Committees During September and October 1947 of Conditions in Europe, with Particular Emphasis on the United States Information Service,” November 1947.

This report opened with the lines, “Europe today has again become a vast battlefield of ideologies in which words have replaced armaments as the active elements of attack and defense... The lines in this conflict are becoming so clearly drawn that positive American leadership must be promptly exerted to combat the encroachments of totalitarian power politics and to counteract the insidious undermining of free forces resisting communism.” A joint Senate and House committee, under the co-chairmanship of Senator H. Alexander Smith (R-NJ) and Representative Karl E. Mundt (R-SD), visited 22 European countries in September and October of 1947. Their purpose was “to study the political and economic conditions in each [country], as well as our present informational and cultural services” to make the programs more effective to “fully implement United States foreign policy.”

The quote above is important for point 5: to be a ready instrument of psychological warfare when required. In the final version of the report, released by the Senate and the House in January 1948, a week after the Smith-Mundt Act was signed into law by Truman, had six points. A new point was inserted at the front, to “tell the truth”, while the “ready instrument” was reworded to “aggressively interpret and support our foreign policy.” The latter is an understandable change considering the State Department’s then (and continuing) aversion to the words “psychological” and “warfare.”

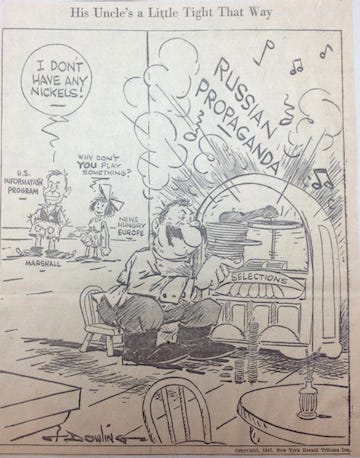

The conclusion of the 19-page preliminary analysis, which covered political and economic conditions, budget issues, and organizational and leadership issues, includes this line: “We should stand on our own feet and stop thinking that a piccolo can drown out a Soviet brass band.” I have a political cartoon somewhere that reflects this, perhaps it is this, but I thought I had one that referred to a piccolo:

This preliminary report, though not released to the public, was the basis of an article published in the New York Times Magazine attributed to Karl Mundt entitled, “We are Losing the War of Words in Europe.” (Nerd alert: Do you know you can buy reprints of NYT articles? Well, I bought this one and it’s framed and on my wall.) The article's purpose wasn’t to build public support but to get the Senate to move as they were effectively debating the perfect, an admission made by Sen Smith and others in a Senate Foreign Relations Committee executive session a few weeks later. The nudge worked, and they passed the bill, which previously passed the House in June, 292-97 (most of the nays came from the “geography of the hard core of isolationism” of both parties). Not coincidentally, Mundt’s article followed one by the head of the UN’s Food and Agricultural Program on the need to meet worldwide food shortages, particularly in Europe, devastated by drought, a severe winter, and war. Besides the humanitarian aspect, the potential repercussions were clear: “Widespread and continuing hunger, with the resulting social and political unrest, will undermine the foundation of governments.” Mundt echoed this point in his article with this paragraph, one of my favorites about aid:

Up to now, we Americans have largely contented ourselves with efforts toward feeding the stomachs of Europe while the Russians have concentrated on feeding its minds. If this formula is continued, it is easy to envisage the result at the end of the trail. We may help avert starvation in Europe and aid in producing a generation of healthy, physically fit individuals whose bodies, are strong but whose minds are poisoned against America and whose loyalties are attached to the red star of Russia. If we permit this to eventuate it will be clear that the generosity of America is excelled only by our own stupidity.

It’s important to recall that the Marshall Plan was announced a few months earlier in a speech that included this statement:

Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.

By the way, the special joint Smith-Mundt committee provided ten suggested areas of inquiry to the Members who participated on the trip. One of ten these seems relevant today:

What and how much propaganda is Russia carrying on? What is the number of persons doing this work? What kind of activity is being carried on, and what is its estimated cost? Is this directed against the United States in the countries you visit? Do the people listen to Russian broadcasts? What are the local information facilities of the Communist party newspapers, radio stations, libraries, etc.? Are they subjected to a large amount of Russian material in the press, movies, libraries, schools, etc.? How large is the Russian program for exchange of students and specialists in their area, and is the Russian propaganda effective?

The other nine are generally much shorter, though they are not softballs. Area of inquiry number six included exploring whether the “present personnel [are] competent?”

Q7:

I am convinced an information program can contribute to our security just as can an army, a navy, and an air force; and that it can make its contribution in a manner that is vastly preferable to the threat or the use of force, and at infinitely less expense.

When: 1946, selected by 47% of the respondents (1941 selected by 9%, 1953 enjoyed 64%).

Source: Testimony of Secretary of State James F. Byrnes before the subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee, April 1946.

Byrnes was requesting Congress support the International Information Programs then operating without explicit legislative authority pending the passage of the then-named Bloom bill, originally introduced by Mundt in January 1945 (see The Incompleteness of the Fulbright Paradox). Preceding his comment above, Byrnes said, “There never was a time, even in the midst of war, when it was so necessary to replace prejudice with truth, distortion with balance, and suspicion with understanding.”

In his November 1947 article mentioned above, Mundt used a common comparison at the time: the price of a battleship. He asked for spending of “just about one-third the cost of constructing a modern battleship under prevailing building rates.” He continued that spending an amount of “just two battleships spread across the next half-dozen years in Europe…[is] an insurance to make our economic aid [the Marshall Plan] program an effective instrument for peace.” In other words, an information program was needed to support our policies.

These programs are inexpensive relative to the deployment and use of destructive force. This statement by Byrnes was echoed repeatedly over the years. The same sentiment is seen in George Gallup’s statement following the demise of the Freedom Academy proposal that I’ve written about (and here) and which

uses to frame writing: “If a country is lost to communism through propaganda and subversion it is lost to our side as irretrievably as if we had lost it in actual warfare.”Q8:

I am sure if you get away from telling the truth, then there is no place where you stop.

When: 1947, selected by none of the respondents (1917 chosen by 50%, 1960 also got 50% of the vote).

Source: Testimony of Under Secretary of State Dean Acheson before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, May 1947.

Acheson was testifying in support of the pending Smith-Mundt bill, commonly referred to then as the Mundt bill. This statement spoke to the reality of the information program, and one that law review articles and academic writings on the Smith-Mundt Act ignore, something I wrote about here in the first of two “unintended and unintentionally long rebuke of two law review articles on Smith-Mundt.” This was followed up by eloquently named: “Follow up to ‘You’ve told us why the Voice, but you haven’t told us what it is.’”

Dean Acheson believed in the information program, a comprehensive program that was far more than the radio operation that gained all of the attention.

Q9:

So long as we remain amateurs in the critical field of political warfare, the billions of dollars we annually spend on defense and foreign aid will provide us with a diminishing measure of protection.

When: 1961, selected by 45% of the survey respondents (1953 chosen by 9%, 1972 got 45% of the vote).

Source: Senator Thomas J. Dodd, speaking in support of the Freedom Academy bill in February 1961.

The whole statement is:

We have lost and lost and lost in the cold war for one primary reason: we have been amateurs fighting against professionals. So long as we remain amateurs in the critical field of political warfare, the billions of dollars we annually spend on defense and foreign aid will provide us with a diminishing measure of protection.

Keep in mind, as I wrote elsewhere (and in greater detail in the book chapter, The Politics of Information Warfare in the US” in Hybrid Conflicts and Information Warfare: New Labels, Old Politics… let me know if you want a PDF of my chapter), the US Information Agency wasn’t even a part of these discussions as it was not charged with or funded to fulfil what the Freedom Academy proposed. It should be noted that at this time, and after, a new report on the deficiency of USIA came out almost annually (this situation was one of the reasons the term “public diplomacy” was adopted in a public relations campaign to defend USIA’s independence, see my Operationalizing Public Diplomacy chapter). One of the three reports completed in 1961 on fixing USIA and its relationship with foreign policy, including its roles and responsibilities and integration with policymaking, was led by the number two at USIA, who urged the agency to “undertake to persuade, not just to inform.” Put another way, the FA proposal would have helped train USIA personnel.

Mundt, now a Senator, was a major proponent of the Freedom Academy. The below statement is part of a long argument on November 8, 1963, in support of the Freedom Academy bill, then a confirmed death at the hands of Senator Fulbright who used parliamentary tactics to pull the bill into his committee and suffocate it. The “they” Mundt refers to below are the many Senators who supported the bill.

But they agree on one thing, namely, that we cannot win a war against professionals if we are relying on amateurs. This does not mean that the amateurs are evil. This does not mean that the amateurs are bad. It merely means that golf tournaments are not won, either, when amateurs are playing against pro- fessionals. It means that football games are not won when amateurs are playing again.st professionals. It means that baseball world champion.ships are ,not won by amateurs playing against professionals. And wars are not won that way. They are not won by arraying amateurs against professionals when the wars are hot. They are not won that way either when the wars are cold. …

The world and the American taxpayer both deserve a program which is effective, which is implemented by personnel who are trained and competent. They need a program which planned and implemented by professionals, and not merely proposed and promoted by enthusiastic, well-intentioned but inadequately trained amateurs.

Q10:

The truth is that a fact — an incontrovertible fact — is often the most powerful propaganda

When: 1946, selected by 8% of the survey respondents (1953 chosen by 67%, 1961 got 25% of the vote).

Source: Elmer Davis, formerly the Office of War Information chief, speaking to the Chicago Rotary Club in February 1946.

I’ll admit that I put in 1953 in the hopes of tricking people into thinking this statement related to the establishment of USIA. I also selected 1961 for a similar reason: thinking some might think Edward R. Murrow said it. Murrow did say something similar, but I think Davis’s comment has more impact, considering the date.

Davis was responding to the aggressive stance by the Associated Press, supported by the United Press (the Hearst news service, International News Services, would not merge with UP to make UPI for some years; and INS did not go along with the AP here), in arguing against a government information program. That broad statement is how you’ll read about the AP’s arguments in academic and law review literature, but the AP was focused on the radio operation and not on the more extensive non-radio information programs to be authorized by the pending Bloom bill, formerly the Mundt bill as mentioned earlier. The radio program provided “spot news” (think today’s headline news), which competed with the AP, in addition to unfiltered and unedited US government speeches and statements. Davis was referring to the plain facts that were and were to be sent, in contrast to the characterization by the AP, namely by its executive director, Kent Cooper.

Anyway, that story gets quite long, including a long effort to remove the radio operation from the State Department and to put it into a non-profit managed by and funded by the government (with a board of bipartisan trustees appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, plus a full-time CEO running day to day operations). I delve into the details of this in my (pending) book. So that is it for now.

Thanks for reading.

Thanks for all this. Your explanations and resources remain the 'go-to' whenever I need to refute the exhortations of those that think 'fixing PD' or re-creating certain defunct organizations is as simple as getting a few million dollars into a line item (usually Defense...to be spent elsewhere). Usually the proponents' heart is in the right place even if the mind remains influenced by whatever seems easiest to believe. Strengthening the psychological/information element remains largely about will and leadership, and not about money.