How it was possible to build and sustain public support for a war effort?

A question asked by American psychologist Gustave Gilbert to Hermann Göring at Nuremberg

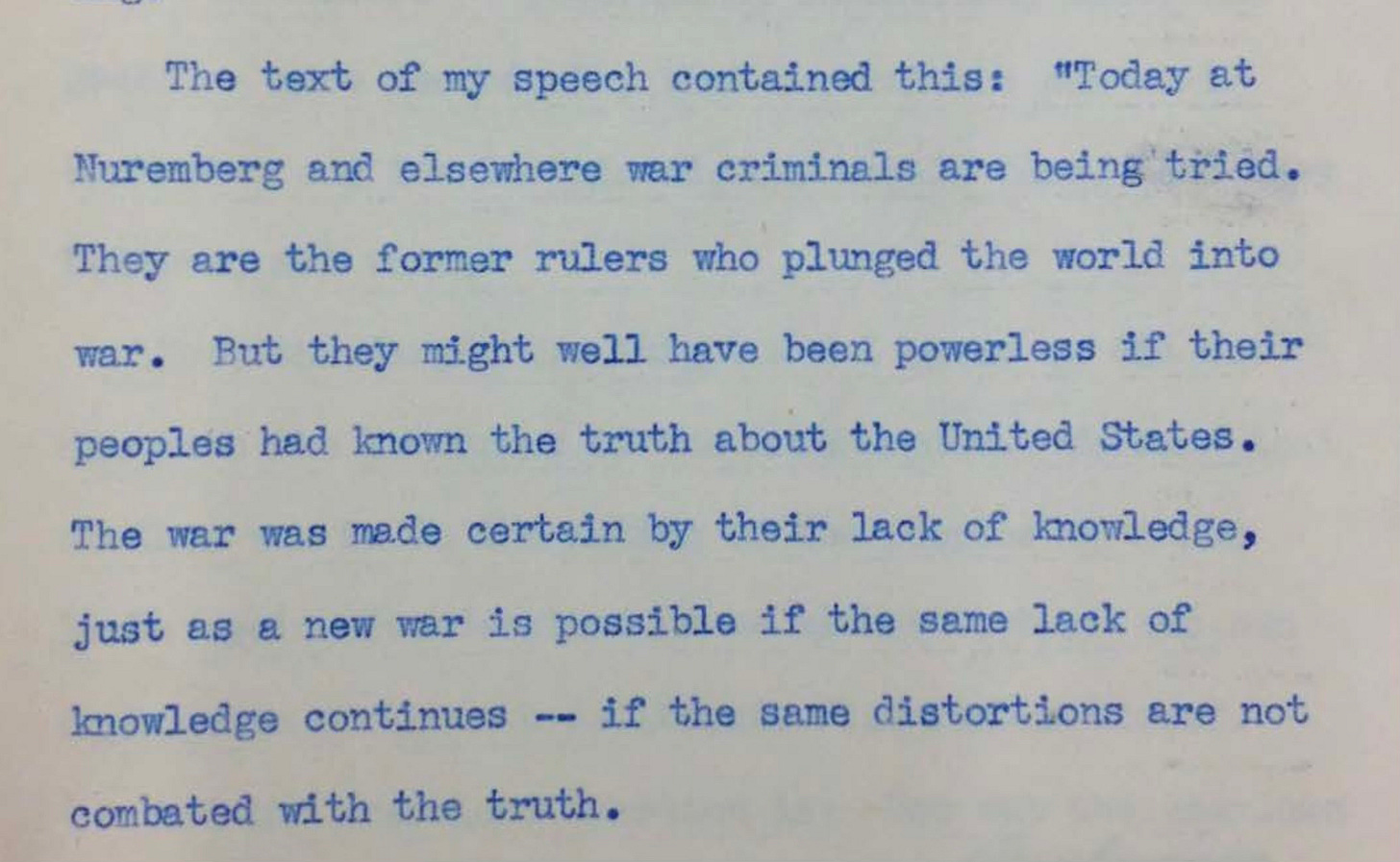

The following comes from my long-in-development-and-not-yet-complete book on the history and evolution of the Smith-Mundt Act. The Smith-Mundt Act, which some may not know about and others may need a reminder of, was a law allowing for the use of truthful information to counter disinformation, correct misinformation, and fill gaps in information through a variety of means, including exchanges, books, films, speaker tours, magazines, the commercial press, and news distribution. When the original legislation was introduced, the purpose was to address these issues, which were then the key lessons learned from the rise and impact of Nazi propaganda. It was not until later in 1946 that the exploitation of these by Soviet political warfare was realized, leading to a shift in the language around the pending bill that would later be known as the Smith-Mundt Act.

Field Marshall Hermann Göring was the highest-ranking Nazi to survive the war, be tried, convicted, and sentenced to death at the Nuremberg Tribunal. Gustave Gilbert, an American psychologist fluent in German working as a translator with the Nuremberg Tribunal, interviewed him in the days between Göring’s conviction and his suicide the day before he was to be hanged.

Gilbert wrote about this and other interviews with other Nuremberg defendants in his book Nuremberg Diary (1947). Gilbert asked Göring how it was possible to build and sustain public support for a war effort, especially in Germany, which had barely recovered from the still recent disaster of World War I. The following is from Gilbert’s book. The italics are Gilbert’s.

“Why, of course, the people don’t want war,” Göring shrugged. “Why would some poor slob on a farm want to risk his life in a war when the best that he can get out of it is to come back to his farm in one piece. Naturally, the common people don’t want war; neither in Russia nor in England nor in America, nor for that matter in Germany. That is understood. But, after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine the policy and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy or a fascist dictatorship or a Parliament or a Communist dictatorship.”

“There is one difference,” I pointed out. “In a democracy, the people have some say in the matter through their elected representatives, and in the United States, only Congress can declare wars.”

“Oh, that is all well and good, [replied Goering] but, voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is tell them they are being attacked and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same way in any country.”

Thanks..hoping I'll be able to fall asleep at a reasonable hour with this lodged in my head late at night.