It's not new, we're just ignorant

Our modern Maginot Line does little against political warfare

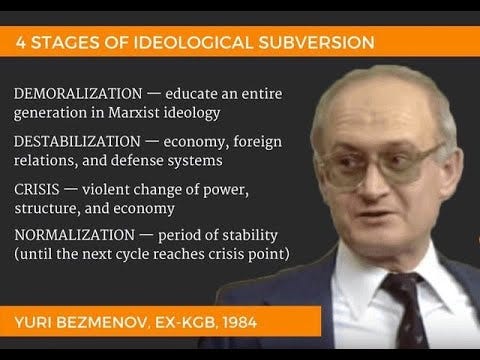

In the early 1980s, a Soviet defector gave lectures and interviews on “ideological subversion,” which, he noted, could also be called “active measures” or “psychological warfare.” I would add it could also be referred to as political warfare. In public engagements, Yuri Bezmenov described the four stages of this ideological subversion that intended to change how target audiences perceived reality. For an overview, see the interview below; for a deeper dive, see this one-hour lecture he gave in 1983.

Two weeks ago, I had the pleasure of sitting on two panels at the Connexions24 conference in Austin, Texas. For the first panel, “From Reactive to Proactive: The United States & Information Warfare,” I spoke a bit about the misunderstanding of “information warfare,” a term that tends to focus minds on a munition and thus how to “counter” that munition rather than the myriad of other salient issues related to the aggression, and the more fitting label of political warfare. I also spoke about the need to fix the pipelines to leadership – the schoolhouses, from public administration schools to political science to international relations and beyond – to expand the aperture and include the role of public opinion in foreign affairs and national security. I pointed out that political warfare is cheap asymmetric engagement that our adversaries would be stupid not to use, especially since they’ve suffered virtually no repercussions. It enables them to bypass the Maginot Line of our military deterrence, where we’ve placed virtually all of our proverbial eggs of national defense. I shared that I didn’t come up with the Maginot Line analogy myself, but rather, I began using this reference after reading a 1955 article on the gray areas and military deterrence by a guy the audience likely heard of, Henry Kissinger. I had the opportunity to discuss the propaganda of the word propaganda and its damaging effects on understanding, education, organization, and policy.

As it is my habit of emphasizing the issues of today are not new, I shared two quotes from the past as part of my eight-or-so-minute opening and in the Q&A.

Why should a leader, who was so keenly aware of the political and ideological significance of the war, have felt that the way to win it was to ignore its political and ideological aspects?

This is from 1946 as the author looked forward to the post-war world. It is a serious question that deserves an in-depth discussion, which is something for another time. It remains a fitting question today. Next.

We have lost and lost and lost in the cold war for one primary reason: we have been amateurs fighting against professionals. So long as we remain amateurs in the critical field of political warfare, the billions of dollars we annually spend on defense and foreign aid will provide us with a diminishing measure of protection.

I’ve shared this before on these pages. It’s from Senator Thomas J. Dodd arguing in support of something called the Freedom Academy (from which

is named) in 1961. The FA was to be under an independent federal agency established to provide analysis and instruction on adversarial political warfare to educate US government and civil society leaders, and the same in allied nations, to anticipate and proactively pre-empt, or at least be better at reactively countering adversarial actions.Bezmonov came up during the Q&A of my second panel, “A World Wide Web: Countering Foreign Interference & Information Manipulation.” My friend Jeff Trimble asked for my thoughts on Bezmenov’s four stages of ideological subversion, which Jeff read out. You can hear Jeff’s question at about the 1:15 mark in the video below, followed by my response and that of my fellow panelists.

It is probably safe to say that many would view the statements from the early 1980s and the general principles they represent as revelatory. I agree, but not because of the reasons most probably think. The revelation here is the perceived reality that this was new then or is new now. Not everyone thinks that, of course. See Todd Leventhal’s

, Timothy Snyder’s , Thomas Rid’s work, and Asha’s substack, which I mentioned above, are just a few names in what might seem like a long list but is actually a relatively small cadre. I feel that I could, with relative ease, compile a longer list than what might be compiled today of authors who, in the 1940s through early 1960s, wrote extensively on this topic from informed positions, having served in – including the executive and the legislature – and near government, and raised serious alarms from the government’s inaction.Finding a report or conference discussion that thinks everything is new is not difficult. The technological evolution is relative, as similar concerns about social media today were raised about the telegraph in the 1890s, with relatable fears from the reduced cost of moving people and ideas around the world, and penetrating borders and bypassing traditional gatekeepers, with increasing speed surfacing nearly every decade thereafter. Possibly another new thing is that Russia and China, lacking any real penalty for their actions, don’t need to expend the energy to cover their tracks. On the whole, the means and objectives aren’t new. Far from it. The surprise someone might avoid the Maginot Line is evergreen. The only really new thing is the proverbial call now often comes from within our house.

Dealing with adversarial political warfare did not fit – and still does not fit – the concept of international relations as perceived by the United States today and yesterday. The threat has been ignored, minimized, dismissed, and allowed with limited repercussions, often because of fears the adversary might escalate its aggression. When addressed, it is usually through covert means. Through national security policy priorities, budgets, and organization, the US government continues to reveal its lack of interest in arming itself for the war it is now and has been in.

So, how did I respond to Jeff’s question about the Russian concept of ideological subversion that surfaced in the 1980s? Revealing whatever shock his comment may have had was the result of a perceived reality in the US government, an indifference inculcated by foreign policy education and bureaucratic inertia that discounted the political warfare, or whatever you want to call it, waged against US interests for the past nearly eighty years. Naturally, I replied with a statement from 1964. What I recited is the bolded bit below, with more of the Congressional testimony from which it was drawn included for context.

I submit that a new agency of this type as outlined in H.R. 5368 is called for, because the conflict itself is of a new type unprecedented in the history of this Nation, a type of conflict for which we are very poorly organized. We have been conducting the cold war as if it were a traditional conflict between great-power interests. This type of conflict, with which the 19th century has made us familiar, turns on territories, boundaries, and the imponderables of a nation’s position among other nations. Its ultima ratio is a military test of strength, for which nations prepare through armaments and alliances. In this kind of conflict, one tries to protect one's interests while avoiding war as much as possible. If war breaks out, though, one fights it until a peace treaty is achieved, after which the contestants continue as nations, albeit in different political circumstances. …

In the cold war, it not boundaries and territories, spheres of influence and relative power which are at stake, even though all these play certain role. Nor war the ultima ratio of this struggle. Nor is a peace treaty the prospective outcome if war should break out. The Communists are fighting to dissolve, decompose, disintegrate, and destroy our society, institutions, authorities, and habits of thought and heart. We are fighting to free our society from this kind of assailant. The Communists do not look on war as their chosen means to obtain their ends. In all their history, they have opted for a minimum of force when coming to power, and for a maximum of force and terror only after they had secured full control of the public means of compulsion. They have gained access to these means mostly with the help of allies with whom they were united in coalitions and whom they destroyed as soon as they had become public officials.

Internationally, the same is true. We have armed ourselves and successfully maintained a formidable alliance. We have deterred the enemy from any large-scale military attack on us. But in the Middle East, Africa, South Asia, and Latin America the Communists have established new positions of strength without military attack. Our military ramparts are still strong. But the enemy has moved underneath and around them, even in our midst, creating a neutralist movement directed against the possession or use of nuclear weapons. These are not the methods of conventional great-power conflict. We are fighting an enemy who controls a nation and often looks like that na tion's representative, but has aims and motives quite different from those of a national government. We are threatened by an intent that assaults not merely our power but our way of life. And we are confronted by methods of persuasion, manipulation, and subversion the like of which no great nation has faced before.

I am saying all of this in order to establish to some extent the reason why we have done poorly in the cold war so far. I believe that this is not due to any “softness on communism” in leading circles, as has been often alleged, but simply to a confusion of the cold war with a traditional great-power conflict. And that confusion I do not think stems from sinister motives. The truth is that our Government is now organized in its external capabilities to meet the kind of threat that is involved in a traditional great-power conflict, the only kind of power conflict with which we have been familiar.

The above is one of many statements I’ve identified over the past dozen years that could easily be repackaged with minor editing as a presentation today. (I did this once… about 80% of a presentation was from 1946.) The speaker was Dr. Gerhart Niemeyer, then a political science professor at Notre Dame. He previously served at the State Department, had been faculty at the National War College, and had also been faculty at Yale and Columbia Universities. I could have drawn from Niemeyer’s 1959 testimony on the same issue or from countless others, but the above provided a concise reply. I hadn’t shared Niemeyer’s quote before, so it was something fresh. And yes, he’s arguing in support of the Freedom Academy above, as he also did in 1959.

As for the old tried and true, here are two quotes I first used publicly in a January 2017 War on the Rocks article. The first is from 1962 by Senator Karl Mundt, formerly Representative Mundt.

We train and prepare our military people for the war which we are not fighting and which we hope will never come, but we fail to train our own citizens and our representatives abroad to operate in the cold war — the only war which we are presently fighting.

The second is from 1963 by a group called the Orlando Committee. It expresses their disappointment at the expected death of the Freedom Academy concept at the hands of Senator J. William Fulbright.

Someday this nation will recognize that global non-military conflict must be pursued with the same intensity and preparation as global military conflicts.

Both remain fitting testaments to the present. Worse, there is no indication of change on the horizon, either from the executive or the legislature. The result is essentially grassroots efforts across government to adapt as they can to the historical lack of strategy, priority, integration, support, and resources from decades of decisions from the many occupants in the Oval Office through the more numerous cabinet secretaries on down.

Thanks for reading.

Sent. By the way, I suggest listening to the audio for Session One, Panel 1 for Filimonov's presentation: https://soundcloud.com/warstudies/kcsc-panel-1?in=warstudies/sets/kcsc-conference The PPT I sent (to the at the mac dot com address I have) was his.

Illuminating article, Matt. Timely too. Bezmenov’s warnings from years ago about “ideological subversion” help to confirm and clarify my growing concern that America is under a corrosive slow-motion below-the-radar cognitive attack — a systematic attack from within and afar — in ways you and Bezmenov note, in accord with his four stages of a subversion strategy: 1) demoralization, 2) destabilization, 3) crisis, 4) "normalization.”

My sense, however, is that the strategies and tactics that Russia is using today go beyond and are broader than ”information warfare” and “political warfare.” They reflect what Arquilla and I called “netwar" in our old RAND analyses — netwar being an information-age mode of conflict short of war in which the protagonists use network forms of organization, doctrine, strategy, and related technologies.

I gather (but lack sufficient sources to fully verify) that sometime last decade or earlier Russian theorists and strategists, after first attributing the so-called Color Revolutions and Arab Spring movements to U.S. usage of Gene Sharp's non-violent pro-democracy playbook, later claimed explicitly that U.S. applications of “net-centric” and “netwar” strategies were what lay behind the collapse of the Soviet Union and the diminution of Russia during the late 1990s and into the early 2010s.

Today, Moscow seems to be replicating netwar strategies, including through political warfare, in its efforts in order to amplify our homegrown disarray and to cultivate cohorts near and far. And they are doing so in the slow-moving sub-rosa ways you and Bezmenov illuminate.

I agree with you that “Someday this nation will recognize that global non-military conflict must be pursued with the same intensity and preparation as global military conflicts.” Now is the time to do so, and yet it’s still puzzlingly anguishingly difficult to make a case that gets heard and acted upon.

Onward.