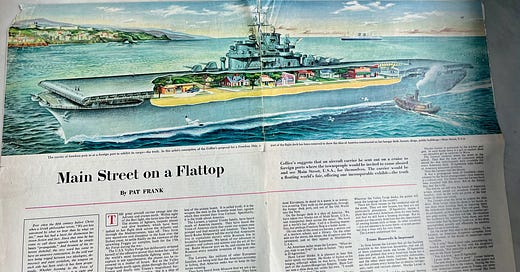

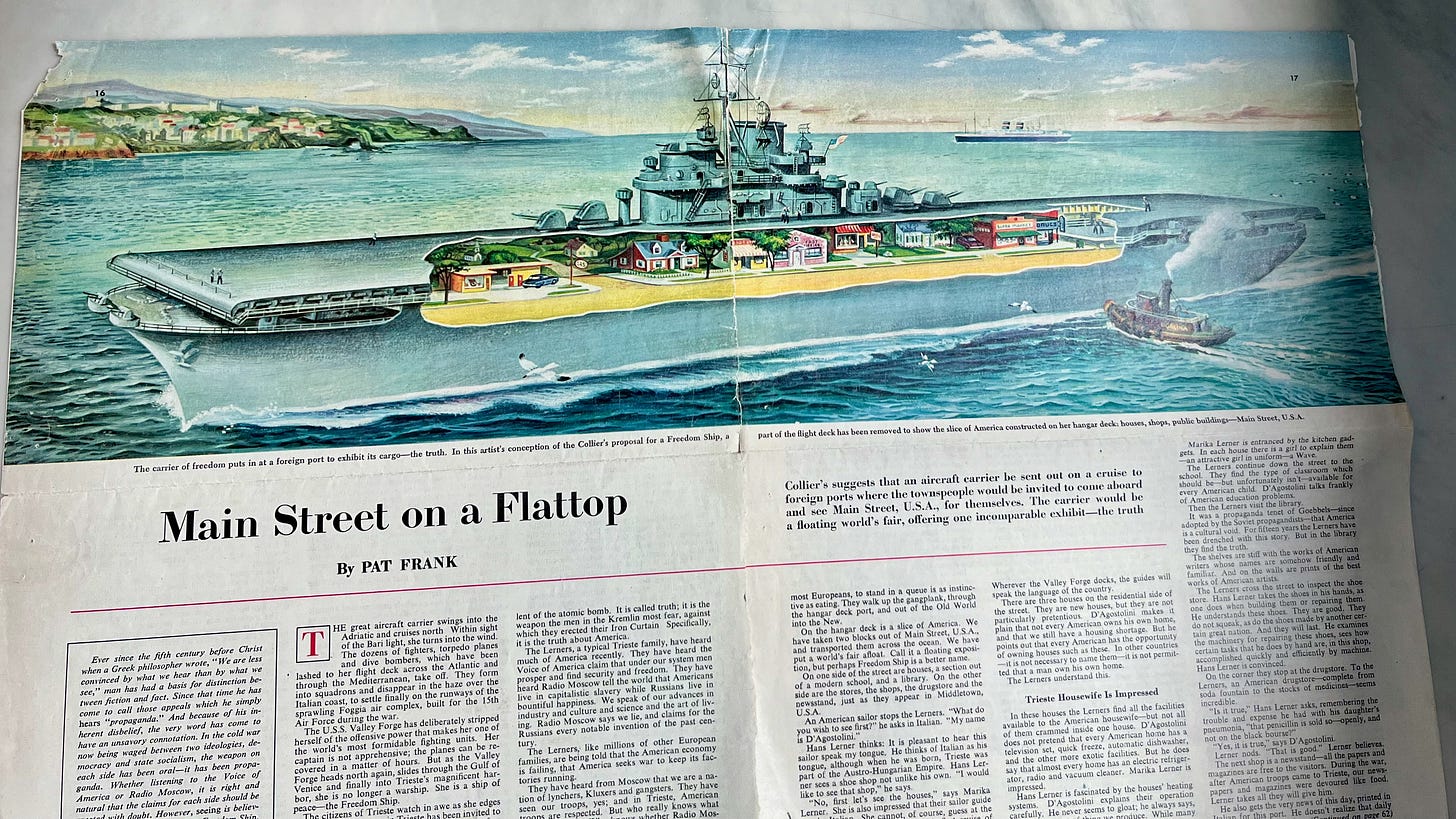

Main Street on a Flattop aka Operation Flattop

Shipping a "typical American town" around the world in a carrier to counter disinformation and fix misinformation about the US and democratic life

Appearing in the November 27, 1948, edition of Collier’s, a popular weekly magazine, was an interesting story about converting the aircraft carrier USS Valley Forge into a floating exhibition about the United States. Built for the war but commissioned more than a year after hostilities ended, the ship would hold a functioning Main Street, USA and tour the world, showing people in other countries what the US was really like. Russian disinformation campaigns and less-aggressive but still damaging misinformation abounded, causing political, societal, and economic strife.

The article imagined the re-worked ship traveling to Trieste, Italy. Before making port, the carrier’s planes, stowed above deck, flew off to a local air base.

The U.S.S. Valley Forge has deliberately stripped herself of the offensive power that makes her one of the world’s most formidable fighting units. Her captain is not apprehensive; the planes can be recovered in a matter of hours. But as the Valley Forge heads north again, slides through the Gulf of Venice and finally into Trieste’s magnificent harbor, she is no longer a warship. She is a ship of peace—the Freedom Ship…

…on the Valley Forge we have something besides guns and ammunition. On the hangar deck of the carrier we have a secret weapon. It is the equivalent of the atomic bomb. It is called truth; it is the weapon the men in the Kremlin most fear, against which they erected their Iron Curtain Specifically, it is the truth about America.

The planes were on the flight deck because the exhibition space was below. And quite the exhibition space it was to be.

On the hangar deck is a slice of America. We have taken two blocks out of Main Street, U.S.A., and transported them across the ocean. We have put a world’s fair afloat. Call it a floating exposition, but perhaps Freedom Ship is a better name.

On one side of the street are houses, a section out of a modern school, and a library. On the other side are the stores, the shops, the drugstore and the newsstand, just as they appear in Middletown, U.S.A.

All of Trieste are invited to the ship. In the story, D’Agostolini, an American sailor speaking Italian, guides a Trieste family, the Lerners, through the scenes.

There are three houses on the residential side of the street. They are new houses, but they are not particularly pretentious. D’Agostolini makes it plain that not every American owns his own home, and that we still have a housing shortage. But he points out that every American has the opportunity of owning houses such as these. In other countries—it is not necessary to name them—it is not permitted that a man own his own home. The Lerners understand this.

They explore a house with its electric refrigerator (“almost every [American] home has an electric refrigerator, radio and vacuum cleaner”). They discuss kitchen gadgets, explained not by the sailor but “an attractive girl in uniform—a Wave.” Then they visit the library where there are plenty of books and “prints of the best works of American artists.”

It was a propaganda tenet of Goebbels—since adopted by the Soviet propagandists—that America is a cultural void. For fifteen years the Lerners have been drenched with this story. But in the library they find the truth.

They visit several businesses on this Main Street in the flattop.

The Lerners cross the street to inspect the shoe store. Hans Lerner takes the shoes in his hands, as one does when building them or repairing them. He understands these shoes. They are good. They do not squeak, as do the shoes made by another certain great nation. And they will last. He examines the machinery for repairing these shoes, sees how certain tasks that he does by hand are, in this shop, accomplished quickly and efficiently by machine. Hans Lerner is convinced.

On the corner they stop at the drugstore. To the Lerners, an American drugstore—complete from soda fountain to the stocks of medicines—seems incredible. “Is it true," Hans Lerner asks, remembering the trouble and expense he had with his daughter’s pneumonia, “that penicillin is sold so—openly, and not on the black [market]?

Then they visit the newsstand, stocked with newspapers printed on the ship for Trieste.

Overall, it’s quite the story of literally shipping a “typical American town” around the world to “exemplify the American Way of Life,” as it was described in a December 7, 1948 meeting of the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff. And yes, George Kennan was serving as the Director of the Policy Planning Staff at the time, and he was present.

The program was to be financed and organized by American businesses but under the supervision of the State Department.

Operation Flattop fit the imperative identified in NSC 4, signed December 18, 1947, which said, in part,

The USSR is conducting an intensive propaganda campaign directed primarily against the US and is employing coordinated psychological, political and economic measures designed to undermine non-Communist elements in all countries. The ultimate objective of this campaign is not merely to undermine the prestige of the US and the effectiveness of its national policy but to weaken and divide world opinion to a point where effective opposition to Soviet designs is no longer attainable by political, economic or military means. In conducting this campaign, the USSR is utilizing all measures available to it through satellite regimes, Communist parties, and organizations susceptible to Communist influence.

The US is not now employing strong, coordinated information measures to counter this propaganda campaign or to further the attainment of its national objectives. The extension of economic aid to certain foreign countries, particularly in Europe, is one of the principal means by which the US has undertaken to defend is vital interests. The nature and intent of this aid and other US contributions to world peace is unknown to or misunderstood by large segments of the world's population. Inadequate employment of information measures is impairing the effectiveness of these undertakings.

The State Department’s Office of Public Affairs, lead by the career foreign service officer George V. Allen, reviewed the Operation Flattop concept and, acknowledging limitations, suggested further consideration. Bear in mind that this office and the Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs had far greater authority over a vastly larger portfolio than the USIA Director, established in 1953 and disestablished in 1999, would ever enjoy, with the same being true for today’s Assistant Secretary of State for Global Public Affairs (as the office has been renamed, apparently) and the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs.

The Public Affairs Area believes that the Department of State must consider “Project Flat-top” in respect to:

a. U.S. foreign policy

b. The existing U.S. Information Program in support of foreign policy.

The Public Affairs Area believes the Department of State should indicate its approval of the objectives of “Project Flat-top” which are presumed to be:

a. To present a faithful picture of a section of everyday American life,

b. To portray the fruits of a healthy economy based on democracy and, therefore, by implication to further the progress of the European Recovery Program.

But there were pitfalls. “Careful planning is necessary” and the potential “possibility of serious negative developments” must be considered.

a. U.S. efforts in the field of propaganda have heretofore been discreet and have had a character of service and interest to the other countries involved: e.g., exchange of students, professors and technicians, libraries; information for government officials, press, educators. The exclusively propaganda nature of the “flat-top” project might well be resented, particularly since the most recent spectacular project involving ships from America was the “Friendship Train,” a welfare project, a gesture from the people of the U.S.A. to the people of Europe (France, Italy, Germany).

b. The use of an aircraft carrier, the appearance of which may be disguised, but the identity of which cannot be concealed, may arouse unfavorable cement in the area visited.

c. Too splendid a presentation may induce in some countries disbelief, in some countries envy, in some countries resentment.

d. Too commonplace a presentation may result in disillusion.

e. U.S. industry may not support the project which, once endorsed by the State Department, becomes in part its responsibility to carry out.

f. U.S. industry may respond satisfactorily from the financial viewpoints but may express dissatisfaction with the scope, or manner of presentation.

The enumerated advantages were not as numerous, but they were significant.

“Material objects are more effective propaganda, in many cases, than word.”

“Such a project can reach people who do not read newspapers, or whose newspapers are heavily censored, or who do not listen to tho Voice of America.”

“The spectacular nature of the project assures extraordinary attention and unusual publicity, producing an important secondary propaganda effect.”

Public Affairs’s list of requirements and planning principles to qualify the project went from a-i, with several sub-bullets, including:

a. That every effort be made to give the project a non-propaganda primary objective, e.g., filling the hold of the ship with supplies for schools (paper, pencils, chalk, maps, copy books) for distribution at the ports visited, or use of the ship for the transportation of students during the season when shipping is at a premium. The propaganda presentation would be much less likely to provoke resentment if it appeared to be the secondary of the cruise.

f. That control of the personnel aboard the ship be the responsibility of the Department of the Navy, officers of which should br instructed to emphasize the possible unfavorable impact on United States foreign policy of undisciplined behavior afloat or ashore.

g. That the itinerary be confined, at first, to the smallest area practicable, possibly northern or western Europe, with a view to determining reactions to the project before a wider area is visited.

h. That a system be established for the limitation of visitors to the exhibit with a view to preventing overrunning by mobs or “packing” by elements hostile to the United States.

State provided a well thought approach to the program. However, four months later, on April 18, 1949, the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, George V. Allen, a career foreign service officer and the third person to hold the position since it was established in December 1944, wrote to his staff about “Operation Flattop” they could ignore the idea, at least for now.

I understand from my last talk with Mr. Beck that he himself was dubious about the effectiveness of the “Main Street on a Flattop” project. He seemed dubious, in fact, that anything could avoid increasingly hostile relations between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. I think we can presume that the project has been dropped unless we hear something further.

Mr. Beck was Thomas H. Beck, the president of Collier’s. It was apparently his idea, or at least was its chief private sector cheerleader.

Though the State Department was interested in pursuing the idea, the Navy Department was less interested. The Navy, according to a memo to Public Affairs from Policy Planning, “did not have any commitment to supply a carrier and crew and to finance the operation” and, State further learned, “would find it difficult to get a crew together, and that they had absolutely no funds to pay for activating, reconditioning, and for fuel and other operating expenses.” There were also concerns that the maximum clearance in the hanger deck may pose challenges to the proposed buildings, plus concerns over the “very real problems of carrying any female personnel aboard.”

“Main Street on a Flattop” would have been something. I can’t help but wonder, however, if something might not have happened to the ship. The Russians were very worried about what today we call an information war. On March 26, 1947, for example, the Associated Press reported the State Department’s Voice of America “is finally making itself heard in Russia.” Operating under the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, VOA had started experimenting with broadcasting to Russia early that month, but there had been trouble. On March 27, it was discovered that the doors to VOA’s transmitter in Munich carrying the Russian language broadcast “had been broken and the switch of the antenna had purposely been ‘reversed’ so that it was directed to South America rather than to Moscow.” (VOA then had six antennae at that Munich site.) In violation of international law, the Soviet Union began jamming VOA in April 1949, suggesting the US was winning the “war of ideology” by that point. What might the Russians have done to the ship? State was well aware of the possibilities of subversive action against the ship, as could be seen in its review of the program. We’ll never know, but now you know about the proposal that was seriously considered to convert an aircraft carrier into a weapon of public diplomacy.

Matt- This is really interesting. Never knew so much was involved into Valley Forge’s history. I appreciate you sharing this. Hope you’re well this week? Cheers, -Thalia

Presumably not included: a large sign directing foreign visitors to leave the town by sundown and the second Main Street USA for non-whites under threat of death.

One wonders if such visitors would have been allowed to eat in the restaurants of the floating Main Street USA. Perhaps a Bull Connor re-enactor could interrogate visitors about the racial compositions of their families before entering, for the authentic experience!