Analyzing "information campaigns" through an anachronistic lens

More on the relegation of information below “traditional forms” of power

A post elsewhere in the substack universe the other week intended to raise warnings about seemingly new threats today’s social media poses. This decidedly underwhelming article intended to level-set fears about such information campaigns. Instead, it proposed “findings” that revealed an anachronistic take on “information.”

Though social media campaigns (or information campaigns as the terms are used interchangeably) are “a feature of modern international conflict,” they are “limited as strategic instruments.” This limit is “because of the difficulty of anticipating the effects that messages will have,” the emphasis being mine. The implication here is that the effects of “more traditional forms of military and economic power,” which are widely considered strategic, are not difficult to anticipate. Segregating the informational effects of “more traditional forms” of power is where this anachronism shines.

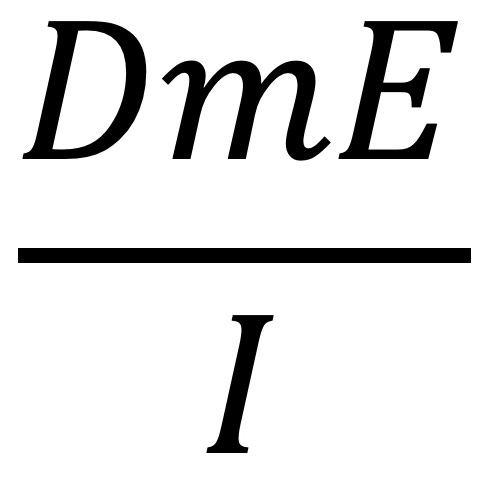

I felt the DIME model of national power reflected in the post. I will not allege the four stovepipes of Diplomacy, Information, Military, and Economics factored into the analysis. I will say the common invocation of DIME today reflects parsing found in strategic analyses such as this post. The concept needs to be revised, with the variations of DIMEFIL and MIDFIELD demonstrating the gross misunderstanding of an acronym derived from an early 1990s organizational chart. If one must refer to DIME, and there is a better – far better – model that I’ve shared before and will discuss here soon, it should be conceived like this:1

In the above model, we see diplomacy, military, and economic power rely on information. While some diplomacy is behind closed doors, much has always been in public to influence decision-making. If its combat potential is unknown, the military has little persuasive or dissuasive influence. The economic power’s reliance – from trade to aid to development and on – on information cannot be understated. The m is lowercase to distinguish it from the “M” of the Defense Department. See footnote 1 for more.

Returning to the post. Common errors exist in the post’s analysis of the referenced information campaigns. The first is the apparent failure to consider the campaigner’s measures of success and return on investment. It is essential to know that informational campaigns are cheap, unlike the more traditional forms of power. They are easily relayed by others (useful idiots, malicious actors not aligned with the campaigner, disinformation profiteers, etc.), deniable, fall below the threshold of a “traditional” response, and, perhaps most importantly, are iterative. These campaigns can evolve and promote multiple themes simultaneously, whether they are absurd, contradictory, or easily disproven. Let’s consider that if you can harass your enemy cheaply and with little to no repercussion, wouldn’t you?

Second, the author, and apparently his co-author for the book the substack post is drawn from, starts with the information campaign rather than the campaigner's political objectives. Third, the informational elements of lines of effort that aren’t the equivalent of hurling a press release into the ether are ignored. Fourth, we can label many of these campaigns, if not all, as political warfare, yet we don’t. Why? Probably because of a general refusal to acknowledge their utility. We were told in this post that they have limited strategic value, after all.

There is a fifth point, but I don’t think it’s relevant here as the post barely scraped the topic of history and institutions. There is a recommendation to “strengthen our own democratic practices,” but at least the post makes no comment on a recommended course of action for when the call is coming from within the house.

I want to return to the focus on social media and step back from this collection of platforms. Let’s return to the basics. There’s no need to step back and consider the pamphleteers and a silver engraver, specifically, who toiled a short distance from where I’m writing this in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Years ago, a warning came from Cambridge that also cautioned about the dangers of new media bypassing the traditional gatekeepers threatening to overwhelm and exploit audiences. Below is that red flag calling out the speed, reach, and subsequent influence posed by new media technologies at home and with regard to international relations.

Moreover, there has been brought forcibly to our notice a phenomenon new in our country, and perhaps in the world — namely, the formidable inflammability of our multitudinous population, in consequence of the recent development of telegraph, telephone, and bi-daily press. I think that fairly describes the phenomenon of four months ago — our population is more inflammable than it used to be, because of the increased use in comparatively recent years of these great inventions.

The above statement is clearly not of a recent vintage. The definition of time and space was in the process of changing with trains, but the nascent automobile would have its mark later, as would flying machines. The above quote was presented in April 1896 and came from the pen of Charles Eliot, then twenty-eight years into an eventual forty-year tenure as president of Harvard University. We find here a reference that a contemporary “tweet,” if you will, could cause a crisis. In this case, it was a comment in the State of the Union speech given by Grover Cleveland on December 2, 1895.2 Cleveland’s speech suggested war loomed, inflaming public opinion. A clarification followed that his comments were more prescriptive than predictive as the issue had, months before, been mitigated.

The issue of psychological defense would rise less than two decades after Eliot’s comments. That is for a different post and a book, however.

History rhymes more than we realize. At some point, we’ll take the past seriously as we look forward. I’m once again reminded of this lament from six decades ago that stemmed, in part, from the segregation and relegation of information from and below the other “traditional forms” of power: “Someday this nation will recognize that global nonmilitary conflict must be pursued with the same intensity and preparation as global military conflicts.”

This other model is over a century old and is actually based on elements of power and not a 1990s organizational chart. The four parts are Political (versus Diplomacy, which represented the State Department), Psychologic (versus the anodyne Information, referring to the US Information Agency), Combat (versus Military, which refers to the Defense Department), while Economics remains the same (which refers to aid, trade, development, etc.). Much of today’s “Military” power is actually political or psychological. DIMEFIL and MIDFIELD should best be thought of as expressions of FOMO: organizations with fear of missing out. They reveal and rely on severely narrow interpretations of D, M, and E.

The SOTU was then given at the start of the new Congress, in this case, on the first day, which started earlier than it does now.

Great post Matt! You did an excellent job pointing out the flaws.

I've come to a similar conclusion. One of the most important sentences in my upcoming book: "Communication is a common denominator and often an antecedent for most forms of social interaction and resultant causality." More specifically, communication technology has monopolized one of the most heavily trafficked social intersections and is often a precursor to almost all judgment and action taken.

"Communication is the fundamental social process" -Schramm

I like this consutruct. I am constantly hearing from folks that "we have an organization in charge of D and M and E, but we don't have an I!"

And you know that's the wrong argument.

Incidentally, this model works well with the Army's conception of information as a part of everything - METT-TC (I).

But didn't you argue elsewhere that DIME isn't about "instruments of national power" but rather structures of bueracracy (or something like that?). Does that even matter here?