Considering the Marketplace of Loyalty

In the marketplace of ideas versus loyalty, focus is easily narrowed on munitions rather than outcomes

Evolutions in modern communications for nearly a century and a half allowed information to reach farther faster. Barriers to information flows, such as time, distance, platform, and language, lessened with each evolution as the ability to transmit information and the cost of doing so plummeted, now to nearly zero. From the transoceanic telegraph to shortwave radio and social media, these evolutions fueled hopes of global integration and understanding. These platforms were catalysts for rapid, sometimes turbulent change as made it easier to access audiences and for audiences to access information. These changes were profound, and relative as we view the telegraph and twice-daily papers of the early 1900s as slow and quaint by today’s standards. Questions and concerns came with the changes: how will—not merely might—these information flows reshape politics and society, especially as the information affects perceptions and beliefs, meaning ideas? The phrase marketplace of ideas emerged in the early period in a court case directly related the new mobility of information. In terms of national security and foreign affairs, should we narrow our focus to something more specific: the marketplace of loyalty?

For a terrific and timely discussion, and background, on the marketplace of ideas, read

’s excellent post:Let’s be clear, though: the marketplace has always been distorted. Despite the comments of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who gave us this term in 1919, the “best” ideas will not and cannot consistently beat out the competition. The scales are always tilted, and what is self-evident may not be known, and it may be subject to intentional disinformation or accidental misinformation. In recent history, in the United States, perhaps the heaviest “thumb” on the marketplace scale (which isn’t a mixed metaphor) is probably Citizens United. For an older example, another distortion was Moscow’s jamming the Voice of America’s new Russian language broadcasts in 1949.1

The difference between the marketplace of ideas and the marketplace of loyalty is the latter focuses attention on the subset of ideas that gain traction and affect behavior in specific ways.

That description can be refined significantly, and you, dear reader, have likely already formulated a better definition. I haven’t really delved into this topic since 2017, when a colleague and I put together a book proposal (co-edited) that found an interested publisher but could not find enough US and non-US contributors.2 At the heart of my earlier effort was the idea that modern communications allowed people to test-drive identities in the privacy of their home or phone. They could adopt or discard whatever they wanted, whether reconnecting with the family’s heritage or exploring a new identity, which may affect the person’s loyalty, as was the case with “Jihad Jane,” the blonde, blue-eyed woman from Colorado years ago.3 The marketplace for loyalty is where specific ideas cause certain actions that concern national security, potentially the concept of nationalism and loyalty. Whether factors that facilitate manipulation, including debt or grievances, should fall within this marketplace is worth further discussion.

One of my favorite references to the marketplace of loyalty comes from 1947. Though it’s not necessary, some background is helpful before sharing the quote. In February 1947, President Truman described the need to supply aid to Greece and Turkey in the face of Russian aggression in clear terms:

One of the primary objectives of the foreign policy of the United States is the creation of conditions in which we and other nations will be able to work out a way of life free from coercion. This was a fundamental issue in the war with Germany and Japan. Our victory was won over countries which sought to impose their will, and their way of life, upon other nations… We shall not realize our objectives, however, unless we are willing to help free peoples to maintain their free institutions and their national integrity against aggressive movements that seek to impose upon them totalitarian regimes. This is no more than a frank recognition that totalitarian regimes imposed on free peoples, by direct or indirect aggression, undermine the foundations of international peace and hence the security of the United States… The peoples of a number of countries of the world have recently had totalitarian regimes forced upon them against their will. The Government of the United States has made frequent protests against coercion and intimidation, in violation of the Yalta agreement, in Poland, Rumania, and Bulgaria. I must also state that in a number of other countries there have been similar developments.

The core of Truman’s speech was the severe distortion of the marketplace of ideas and how those translated to loyalty to the state. A few months later, in June, Secretary of State George Marshall described the need to provide aid to Europe for not just humanitarian reasons but also our national security and the broader marketplace of loyalty, which was affected not just by post-war conditions but actively manipulated by Russian political warfare, plus some grassroots resentment.

…it has become obvious during recent months that this visible destruction was probably less serious than the dislocation of the entire fabric of European economy… It is logical that the United States should do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Our policy is directed not against any country or doctrine but against hunger, poverty, desperation and chaos. Its purpose should be the revival of a working economy in the world so as to permit the emergence of political and social conditions in which free institutions can exist.

The sheer destruction, loss of life, and substantial economic, societal, and political upheavals were made worse by international politics and the environment. The peace treaty with Germany and Austria had yet to be finalized, interfering with the rebuilding of the nations. The weather did not help, as a severe drought damaged and decimated agriculture across Europe, with farms, equipment, transportation, labor, and everything else associated with food production and distribution ravaged from years of war.

The following month, in the insulated safety of a Top Secret memo, George Kennan, who had become the Director of a new Policy Planning Staff under Marshall just a few months earlier, frankly described the “Marshall Plan”:4

[A]ny set of events which would substantially restore to people in Western Europe a sense of political security, and of confidence in a future marked by close association with the Western Powers, would itself release extensive recuperative forces in Europe which are today inhibited or paralyzed by political uncertainty. In this sense, we must recognize that much of the value of a European recovery program will lie not so much in its direct economic effects, which are difficult to calculate with any degree of accuracy, as in its psychological political by-products.

To state this publicly, however, would be a self defeating act. For the Europeans themselves, the restoration of confidence must be an unconscious – not a conscious — process. They must come to believe seriously in the real value of such an economic program. Obviously, we cannot say to them that the value of such a program lies largely in their subjective attitude toward it. This would only confuse them and undermine in advance precisely the psychological reaction which we aim to produce.

The marketplace was not neutral; many actors actively distorted it. Russia, its agents, and various aspirants, sought to tip the scales through subversion, disinformation, exploiting misinformation, and fancifully filling gaps in information. Even before this realization of active adverse efforts, the US realized the nation had to at least participate in the marketplace. An internal State Department report completed in July 1945 declared “modern international relations lie between peoples and not merely governments.” This report’s core concepts and recommendations were used to structure and provide further arguements for a post-war international information program.

In 1947, the situation continued to get worse as the severe drought was followed by a harsh winter that threatened access to the already limited food and heating supplies. In November 1947, Sir John Orr, head of the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization, publicly explained in an article in the New York Times Magazine how non-ideological issues would affect and be affected by the marketplace of loyalty:

Apart from the humanitarian aspect of the problem there is real danger that the food shortage will prevent a return to stable, peaceful conditions. People will not support a Government which cannot provide food. Widespread and continued hunger, with the resulting social and political unrest, will undermine the foundation of governments.

This brings us to the quote I teased at the start. In an article titled “We Are Losing the War of Words in Europe,” which appeared alongside Sir Orr’s article, Representative Karl E. Mundt reminds us what happens when we ignore marketplace of loyalty.

We may help avert starvation in Europe and aid in producing a generation of healthy, physically fit individuals whose bodies are strong but whose minds are poisoned against America and whose loyalties are attached to the red star of Russia. If we permit this to eventuate it will be clear that the generosity of America is excelled only by our own stupidity.

Mundt reminded the reader that the “marketplace of ideas” does not adequately prioritize the “So what?” aspect. Marshall, Kennan, and Orr referred to the same ultimate point. Mundt, who had been a school teacher, a school superintendent, and a college instructor, was the co-founder of the National Forensic League (now the National Speech and Debate Association), a prolific writer, and, along with his wife, active in the South Dakota Poetry Society, hammered this point home. Policies, statements, and actions are not self-evident or always known. Timelines, limitations, problems, and intentions can be manipulated to influence the marketplace, especially the perception of these. The distortion can go either way, but typically, it’s the hostile actor, not the positive one, who has the heavy thumb.

It’s interesting that many academics argue US government efforts to mitigate the effects of disinformation and misinformation and fill in the information gaps is “propaganda” that should, by definition, be limited. (I’m referring mostly, but not exclusively, to those claiming the Smith-Mundt Act was intended to prevent the US government from “propagandizing” the public at home.) These analyses always—I cannot recall an exception in my nearly two decades in this area—fail to separate factual news and public statements, such as from Presidents and Secretaries of State, from what the authors perceive as less-than-factual manipulative content and also never provide an alternative for dealing with disinformation, misinformation, and gaps in information beyond imagining there is a perfect, undistorted marketplace where self-evident truths will rise—without any interference—to the top.5

The marketplace of loyalty isn’t a separate marketplace; it’s part of the ideas market. Think of the marketplace of loyalty as focusing the mind on the impact of ideas that raise questions about, for example, national identity, physical security, government secrets, policies, and, well, loyalty to the overall concept of the nation.

Parting shot

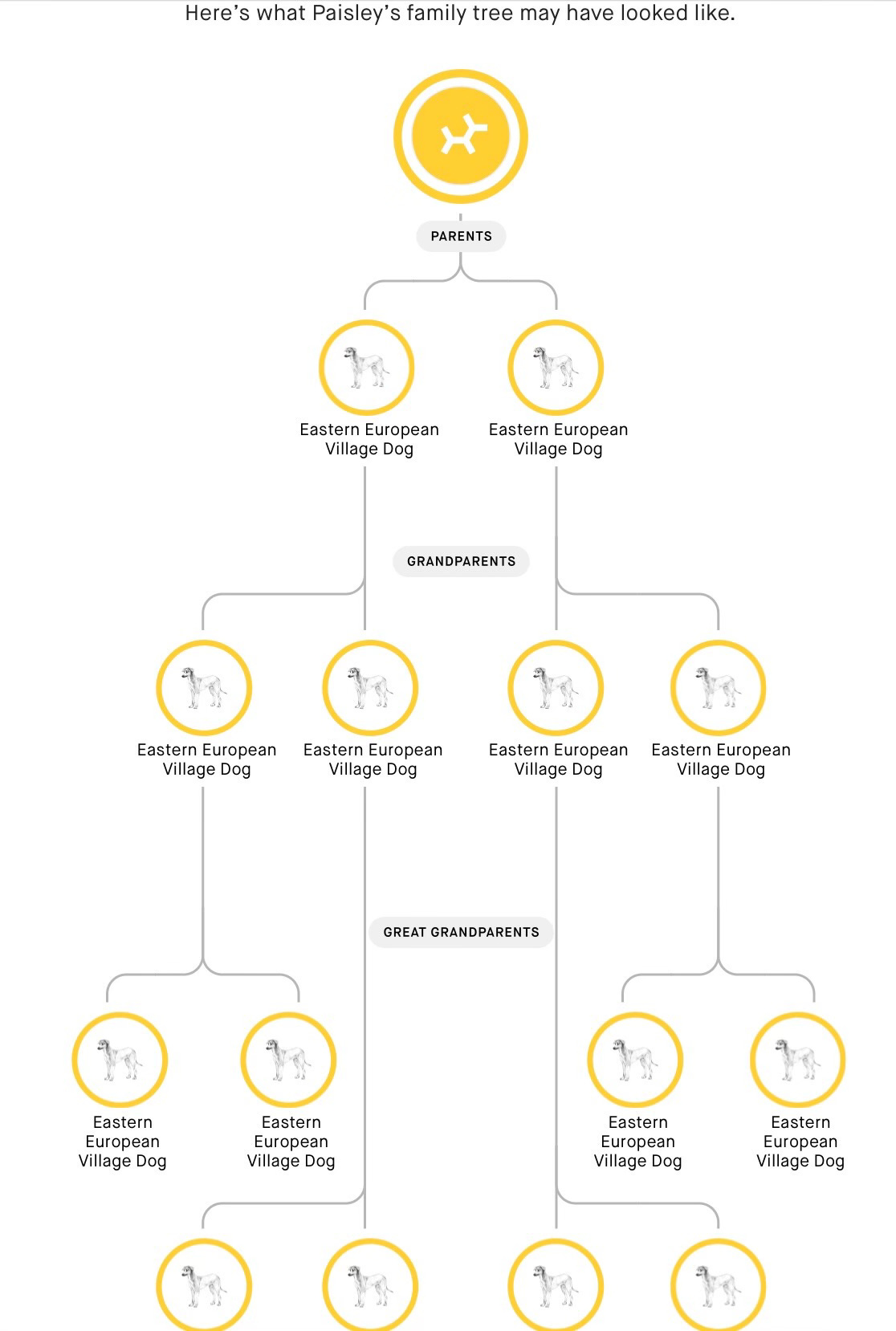

We adopted our dog Paisley, a rescue from a Romanian animal shelter, over eight years ago when we lived in Switzerland. We always wondered about his breed, and of course we were constantly asked what he was (and is, he’s still with us, thankfully).

This week we received the results of his DNA test. He’s… 100%… East European Village Dog. That’s apparently a thing.

Village dogs, like the Eastern European Village Dog, descend from distinct lineages that are separate from modern breeds, like the Labrador or the Poodle. Genetically, village dogs are different from breed dogs. So, his actual breed is Eastern European Village Dog. His ancestors were likely also from the same population of village dogs.

Indeed, based on his DNA, his family tree is straight forward.

Thanks for reading.

I’ll keep my comments on framing the cold war as a “war of ideology” brief. I can argue the Soviet Union acknowledged they accepted their inability to compete when they strictly limited US Information Service materials and libraries immediately after the war, jammed VOA soon after that (after the initial broadcast was delayed when the transmitters were damaged, possibly from sabotage), shut down their borders and those of their satellites, and later led the only military alliance whose only military action was to invade one of its members. Furthermore, every political contest, from mayoral contests to presidents or prime ministers, is a contest over idealogy. Describing World War II as a war of ideology is accurate and useless. Framing the cold war (pre-detente, before the era was a proper noun) as a “war of ideology,” as many historians do, creates false equivalencies between the different parties. Lastly, these same historians almost always (inadvertently?) make statements that dismiss entirely the rote labeling of the period as a war of idealogy. Asserting the war of ideology in the context of the cold war as some kind of level marketplace is absurdly disconnected from the facts of the period.

Our tentative title: “Shifting Identities: How the Marketplace of Loyalties Impacts National Security.” Related to this was an earlier joint effort with a different colleague that resulted in a book chapter: Powers, Shawn, and Matt Armstrong. “Conceptualizing Radicalization in a Market for Loyalties.” In Visual Propaganda and Extremism in the Online Environment, edited by Carol Winkler, and Cori Elizabeth Dauber. Carlisle, PA: Strategic Studies Institute and U.S. Army War College Press, 2014.

Part of my modeling then relied on the idea of hyphens to commas. This reconsidered the hyphenated model (German-American, for example) into commas. This change permits the person to be both German and American, plus a member of other identity groups marketers (specifically adverse or friendly influencers) would seek to tap into and ultimately leverage, like a fan of cricket or a (not US) football club. This comma model permits the permanent or temporary inclusion of identities of someone connecting with an identity group they have an existing link to (like familial or friends) or are interested in.

Kennan’s point here is a core piece of the Marshall Plan that is invariably ignored by perhaps every utterance of the phrase “we need a Marshall Plan” for this or that situation. Missing the fundamental point of Kennan has people thinking they can buy their way to a solution.

These authors also tend, if not always, pin their arguments only on the radio broadcast operations and not the larger information program.