Part I: Why we have the Voice of America

Recalling the realization that delivering factual news & information was a matter of national security

Today’s US Agency for Global Media (USAGM) has a simple and essential purpose: to deliver news and information to undermine the effects of disinformation, misinformation, and the lack of information, including outright censorship, in support of US national security. As to where it does this, since the transition of the Office of War Information’s (OWI) radio broadcast operation to the State Department, directed by the President’s executive order issued before the USS Missouri sailed into Tokyo Bay and effective two weeks later, the basic parameters have been intentional, purposeful, and simple: to supplement, not replace or compete with, private and commercial press. While applicable to other elements of the US government’s international information operations, including those under the United States Information Service (USIS), there was an explicit and intentional emphasis regarding the operation of the radio broadcast element: its operations would be supplementary and facilitative to that of the US press.

There never was a time, even in the midst of war, when it was so necessary to replace prejudice with truth, distortion with balance, and suspicion with understanding... we shall not seek to compete with private agencies of communication, nor shall we try to outdo the efforts of foreign governments in this field. – Secretary of State James F. Byrnes to President Harry S. Truman, December 31, 1945

This is the first part of a (likely) three-part series discussing why we have the Voice of America (VOA) and its sister networks. Part I, what you’re reading now, examines why VOA was kept after World War II. Part II puts forward the argument that had VOA been separated from the government, as the State Department sought, an effort that began in November 1945 and lasted through the summer of 1947, there may not have been a Radio Free Europe (established 1949), Radio Free Asia (first established 1951, reestablished 1996), and Radio Liberty (established 1953). Had the radio operation been separated, the many law review analyses of the Smith-Mundt Act would have to be revised since, though they claim to speak broadly, they are narrowly focused on the unique issues that surrounded VOA. Part III examines the consequences of the disinformation, misinformation, and lack of information on why today’s USAGM continues to exist and its actual and potential value to US national security.

The purpose of this series is to foster a better understanding of why the US had and continues to have one of the largest news agencies in the world, where it operates and why (spoiler: places where accessing or sharing news can lead to jail or death), and what is meant by telling America’s “story” (spoiler: it’s about countering disinformation, not self-promotion or encouraging tourism).

Let me start by putting my cards on the table: USAGM has been and continues to be poorly managed, and similar poor management at VOA. Both have long been unfairly attacked by people whose motivations range from sincere to ignorant to malice. Leadership at various levels, starting at the top, has failed to address valid criticism and concerns about the agency and its operations. I have personal, first-hand experience of severe unpublicized problems as well as significant unpublicized successes. I also firmly believe the agency is more important to US national security than it was from the 1970s through the 1990s.

I write this based on my experience as a Governor on the Broadcasting Board of Governors, USAGM’s prior name, including my extensive interactions with the networks’ chiefs and the operations of the networks in the field, my time in an oversight & advocacy role for international broadcasting operations as the executive director of the Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy, and the twenty years I’ve spent examining, writing about, speaking on, and assisting the US international information activities of several government agencies, including this one, often from inside the respective operations.

In 1945, keeping the radio operation VOA was a tricky concept for the upcoming peacetime.1 There was a clear threat of unfair competition between the deep-pocketed government and the US’s private broadcasters in hiring talent, whether on-air talent, notably non-English editors and speakers, engineers, or anyone else needed to produce and broadcast content. During the war, private stations and broadcasting facilities were commandeered, and now, with peace on the horizon, decisions had to be made for what came after. Complicating matters was international competition for the finite radio spectrum, a looming problem that would worsen. For example, should VOA disappear from the airwaves, even briefly, for whatever reason, there were valid concerns that some other country would fill its place.

On August 31, 1945, Truman issued an executive order that transferred the international information programs of OWI and the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) to the State Department. The President gave the department until the end of the year (only four months) to figure out what elements “should be conducted on a continuing basis.”

The executive order drew from OWI’s advice, delivered two weeks earlier, regarding the “Complete liquidation of the Agency” and transferring the functions that should be kept to other agencies. OWI “emphatically” recommended keeping and placing the general information programs under the State Department, including the United States Information Service (USIS). The radio program, however, was a different beast that needed further discussion.

OWI’s memo, in turn, echoed a State Department 241-page report completed the month before that asked whether the government should have a postwar information program and, if so, what organizational, operational, and fiscal issues should be considered. The inquiry was based on extensive discussions with offices across the government and included discussions with those in the private sector and academia.2 Archibald MacLeish commissioned it in January 1945. Just a few weeks earlier, in December 1944, MacLeish had been sworn into the newly created position of Assistant Secretary for Public and Cultural Relations (renamed in early 1946 as the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs).3 In Congress, Representative Karl E. Mundt, Republican from South Dakota, introduced a bill to promote the interchange of school teachers across the Americas on January 24.4 In short, there was a lot of thinking about the nation’s international information and broader engagement needs, and this was even before Russia’s political warfare, and specifically their disinformation efforts, took off and were recognized.

“It would not be too much to say that the foreign relations of a modern state are conducted quite as much through the instruments of public international communication as through diplomatic representatives and missions.” — ” Archibald MacLeish during his confirmation hearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on December 12, 1944

Keeping a government radio broadcasting operation faced legitimate questions with the clear potential for direct conflicts with private industry. Challenged faced other commercial efforts to reach abroad. For example, affecting magazine, newspaper, and book publishers and the motion-picture industry, “the shortage of dollars abroad and blocked currencies are among the important barriers to the greater diffusion of information about the United States and threaten the continued or expanded selling operations of America’s mass communications industries abroad.”5

That 241-page State Department memo suggested four post-war scenarios for the radio operation: (1) a private corporation with government funding; (2) a government-owned and -operated broadcaster; (3) a mixed government & private operation; and (4) completely stepping away from radio and hoping private and commercial media would step up.

The department opted for option 1: a private corporation with government funding. Work toward this end began in November 1945. The plan and organization took shape over the next several months. A not-for-profit would be funded, at least initially, by the government. A bipartisan Board of Trustees would provide guidance and oversight to the operation. Fourteen of the fifteen Trustees would be appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, with the fifteenth being the Secretary of State or a designated Assistant Secretary. The board would “ensure the character of the broadcasts” and “help win the confidence and support of the Congress and the American people by helping to guarantee the objective and non-partisan character of the broadcasts.” Funding could be supplemented by selling broadcast time, receiving outside contributions, and receiving or contracting for programs produced outside of government.” The board would oversee a full-time Chief Executive Officer (paid a market wage) providing operational leadership. Articles of incorporation were drawn up (naturally, it would be a Delaware corporation), as were lists of potential Trustees and CEO candidates.6

Several Members of Congress, notably Senator Joseph Ball, Republican of Minnesota, tried to privatize the entirety of the information and education programs, not just the radio operation. However, deep concerns over the “disloyalty-subversive question” of possible “Reds” infiltrating the information programs led to other problems. The suggestion that the FBI would conduct “loyalty checks” for the National Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), and whichever other private companies participating in the program created more qualms about taking on a venture that would not be profitable for the foreseeable future. (The Smith-Mundt Act required that the FBI conduct a “loyalty check” on every current and future staff working on the information and education programs authorized by the Act.)

Whether private or public, the need for the radio operation was clear. Frank Stanton, the president of CBS, wrote that CBS’s work with OWI and OIAA during the war “convinced us that one of the best ways of enhancing and maintaining the prestige of the United States among the peoples of the world is by making available to these peoples day-by-day uncolored, undistorted, and truthful information about our own country and our people.” Stanton argued this effort could and should be run by private broadcasters, who “could take over the entire job of broadcasting and programming within sixty days.”

Philip Reed, chairman of the board of General Electric (one of the half-dozen US international radio broadcasters), had a different view:

I am convinced that our country must maintain [an] adequate foreign information broadcast service… I believe that the operation of an international broadcasting service should be in private rather than government hands. The immediate problem appears to be that the private owners international broadcast facilities would be unable to render anything like an adequate foreign broadcast service without incurring very large operating deficits… This means, for the present at least, if an adequate broadcasting program is to be maintained the Government will have to shoulder most of its costs.

The hard reality was when the rubber hit the road, the networks acknowledged they could not do this job alone. The “emergency” situation required some government role. In August 1947, CBS’s Edward R. Murrow told a confidential House Committee on Foreign Affairs inquiry “that private industry could not at present take over completely the job of international dissemination of information. He felt that as long as the competition with Russia in Europe and with Great Britain in parts of South America continued, first-hand information possessed only by the Department of State was essential for the successful guidance of any program of information.”

In mid-1947, the bill to support this organization and thus remove VOA from the State Department was a higher legislative priority for the department than the yet-to-be-passed Smith-Mundt bill that would authorize the rest of the information programs and expansive exchange/interchange programs sought by the department and much of the federal government. Senators had a different opinion.

After the State Department became interested in Mundt’s January 1945 bill, the Democrat Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee took over the bill. Now called the Bloom Bill, it was amended in October to include the information programs following Truman’s executive order of August 31. There were plenty of hearings and a lot of attention to the details. This bill passed the House by a two-thirds vote on July 20, 1946, almost the last day of the Congressional session.

The bill was introduced in the Senate only eight days earlier. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee recommended the bill, stating in its report,

In recent years the major nations of the world, including the United States, have begun to pay attention to the attitudes of other peoples and to the information available to them. It has been increasingly evident that wars start in people's minds, and that free interchange of public information, and of persons and skills, would contribute to an understanding between peoples.

The United States was the last of the major nations to enter this field of public information abroad and educational cooperation. Even now, many of the activities of this sort conducted by the Department of State are sanctioned only by appropriation acts and by Executive Order.

However, the complete lack of preparatory work in the Senate meant the Senate’s Republican leadership blocked any further discussion, let alone a vote, on what they considered a wholly Democrat bill.

In May 1947, in the Republican-dominated 80th Congress (which Truman nicknamed the “Do Nothing Congress”), the State Department asked Mundt to reintroduce his bill, alongside which the department submitted its bill for the private radio corporation. A Senator co-sponsor was sought to avoid the previous year’s debacle. Senator H. Alexander Smith, Republican of New Jersey, agreed to be that cosponsor, provided the radio stays wholly in government and “right in the lap of the Secretary of State, where it seems to belong.” Smith was not alone in his view.

“I am not willing to turn over to Mr. Sarnoff [of RCA and NBC] and Mr. Paley [of CBS] the determination of American foreign policy.” — Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. (July 15, 1947)

For some Senators, the private corporation—to be established as a “foundation”—moved the radio too far from the center of government, even if the Secretary of State was one of the overseeing Trustees. Moreover, events had overcome Stanton’s claim of easy privatization.

In 1947, though CBS and NBC produced more than 40% of VOA’s programming, the broadcasters were content to lease their transmitters and sell content to the government because there was little to no profit in the target markets. In addition to the continuing issue of blocked currency (i.e., profits could not be repatriated), Russia’s active disinformation campaigns were now joined by information blockades.

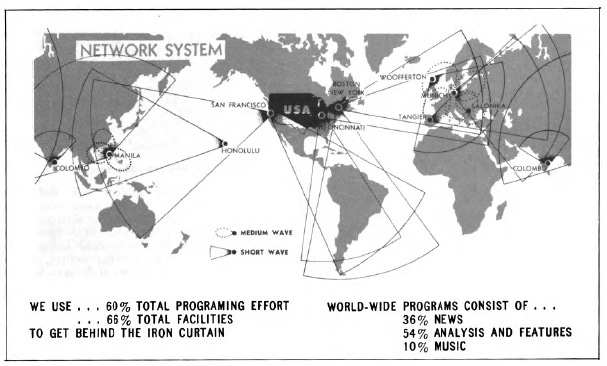

The editor of one of the nation’s largest weekly magazines conducted research and advised the State Department on the question of private enterprises taking over radio service and other elements of the information program. In October 1947, he said it “is naive to say ‘Let private enterprise carry the ball’ and at the same time ignore the fact that there are widening areas in which private enter can no longer operate in a normal manner.” He described a three-part classification system to explain the situation. He called the first group the “Free Zone” where US media “can carry on approximately as usual.” He listed Canada, Cuba, and Mexico as examples. Second was the “Iron Curtain” where “private operation is virtually impossible,” with Russia in this group. Third was “Mixed.” These were “shaky” countries, like France and Italy, “where combined and expanded efforts of government and private agencies are desirable. This group included those with blocked or non-convertible currency, dollar shortages, various resource shortages, etc.

While the government needed to fund efforts into the Iron Curtain and Mixed countries, private enterprises could still provide content. This was written into the Smith-Mundt Act with clear direction from Congress to avoid, or at least reduce, competition with the private sector over personnel and programming. The State Department was directed “to utilize, to the maximum extent practicable, the services and facilities of private agencies, including existing American press, publishing, radio, motion picture, and other agencies, through contractual arrangements or otherwise.”

This led to less department oversight, which, in turn, permitted VOA to broadcast material produced by the private agencies without review. The Smith-Mundt Act was signed into law on January 27, 1948 (three years and three days after Mundt introduced his bill), and within a few months, the limited oversight led to a major embarrassment.

The problem program intended to introduce the US to people abroad by telling America’s so-called story. The audience heard a kind of travel program in 15-minute broadcasts in Spanish with a narrator and two “visitors” exploring the many US states. “Don’t you have a saying that Texas was born in sin but New England was born in hypocrisy?” “Oh, Utah, that’s where men have as many wives as they can support.” “Nevada has no interest in itself—it’s a land of cowboys, and its two principal cities are in competition. In Las Vegas, people get married, and in Reno, they get divorced.”

In the Wyoming chapter, “The frontier day celebration is the most extraordinary festival of the West….” “Look! What magnificent Indian girls!” “Feathered and naked.” “What are they going to do?” “Let me see the program. It’s the 100-meter race…”

The fallout emphasized the importance of government oversight and control and how corporate media may have different objectives and interests than the government. Sharing America’s story could not be a willy-nilly or clumsy endeavor; it required attention to detail and purpose.

Information freedom—both to access and share information—was viewed as a necessary path toward international peace. The key lesson of Nazi propaganda at the time was not the impact of the messages but the Nazi’s elimination of alternative voices that called out the disinformation and corrected the misinformation. To support this, there was a clear need for a radio program to reach into countries where information was difficult to receive or overwhelmed by disinformation or misinformation. The radio complemented the broader information efforts, including those of USIS and the many kinds of exchanges, which were a different form of influence operation. These other information efforts and educational, scientific, or technical exchanges were severely reduced in or ejected from the key target markets, leading to a greater emphasis on the radio.

The international political situation then was remarkably similar to the present, far more so than the structured and routinized 1970s or 1980s. More recently, widespread access to the Internet, like shortwave before it, promised information freedom. The reality is far different, with fantastic manipulation of facts and curtailment of the freedom to access information and speak. More information does not necessarily equate to better information.

For the 1944 presidential election, the Republican and Democrat platforms supported worldwide press and information freedom worldwide. In his article “Pillars of Human Rights,” former Undersecretary of State Sumner Welles wrote that the United Nation’s charter “should contain the specific stipulation that no nation may become a member of the new international organization unless it is able to demonstrate that by its constitution, or by its basic legislation, the citizens of such nation are granted inalienable rights of freedom of worship, of expression and of information.”

While the criteria didn’t materialize, the value of information freedom persisted. VOA was one means of supporting information freedom.

“It cannot be emphasized too strongly that the Soviets and the Communists are today conducting aggressive psychological warfare against us in order thoroughly to discredit us and drive us out of Europe. In order to prevent this, to safeguard our national security, to promote world peace and implement our own foreign policy, based primarily on economic reconstruction, and political freedom, a strong and effective information and educational exchange program is essential… Our Information Service cannot effectively explain our point of view nor deny vociferous falsehoods in a whisper… Hundreds of millions are being expended by the Soviets; and the United Kingdom, although heavily in debt, supports a program employing some 8,700 persons as against our less than 1,400 and costing three times ours. Even little Holland is spending nearly a quarter of a million dollars this year, and spent half a million last year in the United States alone to defend and explain her policies. We are spending just over $30,000 in the Netherlands. It is the opinion of the committee that America is old enough and strong enough to warrant a change of voice—a voice that will rise confidently above the false call of communism.” — Report of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee on the US Information Service in Europe, January 30, 1948

The legislative authority for VOA has always included a sunset clause (Sec 502 of the original Act, 22 USC 1462 today), directing the government “shall reduce such Government information activities whenever corresponding private information dissemination is found to be adequate.” VOA continues to operate in many places worldwide because the “private information dissemination” is not found to be adequate.

However, the lack of real oversight, the absence of leadership accountability, and general confusion by even the well-meaning on how (and even whether) VOA provides value to US national security over many decades have placed the network and the umbrella agency in jeopardy.

As you ponder the purpose and potential value of the agency and its networks, be mindful of the impact of mismanagement, the lack of Congressional oversight, decades of apathy from the executive branch, and the irony that agency narratives are fueled by disinformation, misinformation, and personal grievances on what you think you know about the agency and whether it should continue, and if so, in what form.

In short, you just read a mere glimpse into the discussions around establishing VOA. Are you aware of any serious and inclusive inquiry on remaking the network and its parent agency today? I’m not.7

I would be remiss not to note that it doesn’t take many aggrieved VOA personnel to change the network and umbrella organization radically. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s attacks on VOA relied heavily on one disgruntled VOA employee. Secretary of State John Foster Dulles used this to eagerly eject the broader information service, which Secretary of State Dean Acheson placed within a semi-autonomous organization within the department called International Information Administration. At the time, IIA included half of the State Department’s personnel and more than 40% of the department’s budget. The result was the US Information Agency, “an organization with fewer authorities and less integration than what it replaced.” Dulles believed the information function distracted from his and the department’s diplomacy. We may be on the same track today.

Part II, which will be shorter than this (and will definitely not appear for several weeks), looks at the privatization discussion and asks whether Radio Free Europe, Radio Liberty, and Radio Free Asia would have been separately created if VOA had not been under the staid control of the State Department. This discussion means to tee up the conversation of streamlining USAGM’s five networks into two, or possibly one, to eliminate expensive back-office redundancies that inhibit collaboration and coordination and reduce resources available in the field.

No parting shot (picture) today. This was long enough.

As always, thanks for reading and I welcome your comments, questions, and even criticisms.

I intentionally refer to the pre-State Department VOA as a “radio broadcast operation” or similar because that is how the radio operation was referred to in internal documents. The operation ran a program called the Voice of America, but the VOA name didn’t customarily apply to the entire broadcast operation until early 1946.

The author of this report, Dr. Arthur MacMahon, was a prominent political scientist focused on public administration, primarily teaching at Columbia University. At the time, he was a consultant to the department. He was president of the American Political Science Association, editor of Political Science Quarterly, and founding member of the American Society of Public Administration. Unfortunately, his insights into the department have been largely forgotten. I recommend his book Administration in Foreign Affairs (1953).

Before this office was established, the public information role was held by the department's assistant secretary in charge of administration. If you think this is odd, consider that Woodrow Wilson’s second Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, placed this responsibility under the department’s counter-intelligence chief.

Mundt sent his bill to Nelson Rockefeller, head of OIAA, who forwarded it to MacLeish. MacLeish discussed the bill with Dean Acheson, a close friend from their days at Yale. MacLeish followed up with Mundt on February 7, writing that he was “tremendously interested” in the bill and that the “whole matter of international student exchanges relates very closely…to the work of some of the Divisions” under his office. MacLeish continued that he would like to have lunch and get more of Mundt’s ideas, “not only as a Member of Congress, whom even Dean Acheson holds in awe, but as a man with a long, practical experience in education.”

Addressing this problem temporarily stalled the Smith-Mundt bill in the Senate. However, Senators decided perfection was the enemy of the good, so they chose to pass the bill that the House passed months earlier and amend the Act later. That later amendment created the Informational Media Guarantee program.

The “Top List of Preferred Names” included Mark Ethridge (“Very respected by the Broadcasting industry” and “A liberal journalist…regarded as a southern journalist”); Roy Larson, President of TIME; Ed Murrow (“Paul [Porter, former FCC chairman] and I [Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs William Benton] are afraid of Bill Paley [head of the Columbia Broadcasting System] because of the [David] Sarnoff [head of RCA, which owned the National Broadcasting Corporation] angle, and Ed Murrow seems to be a very happy idea.”); Milton Eisenhower; John Foster Dulles (“That would be a typical British appointment, I think, trying to educate a possible successor.”); Anna Rosenberg; and Oveta Hobby. The “Class B” list included Arthur Sulzberger, C.D. Jackson, and Joseph Kennedy. George Kennan and Loy Henderson were floated as CEO candidates.

Not to mention the successor to the Assistant Secretary of Public and Cultural Relations, renamed in 1946 as the Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs, is the current Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs (with the Director of the US Information Agency inserted in there 1953-1999), a position that has been so disregarded that it has been without a confirmed officeholder more than 40% of the time it has existed.

Thank you for writing this short history. We need VOA domestically and abroad more than ever. I’m sure Kari Lake will do a spectacular job undermining the foundations of VOA.