Political warfare: the obvious choice against our Maginot Line

Our ignorance isn't new and our failure to respond isn't because USIA was abolished

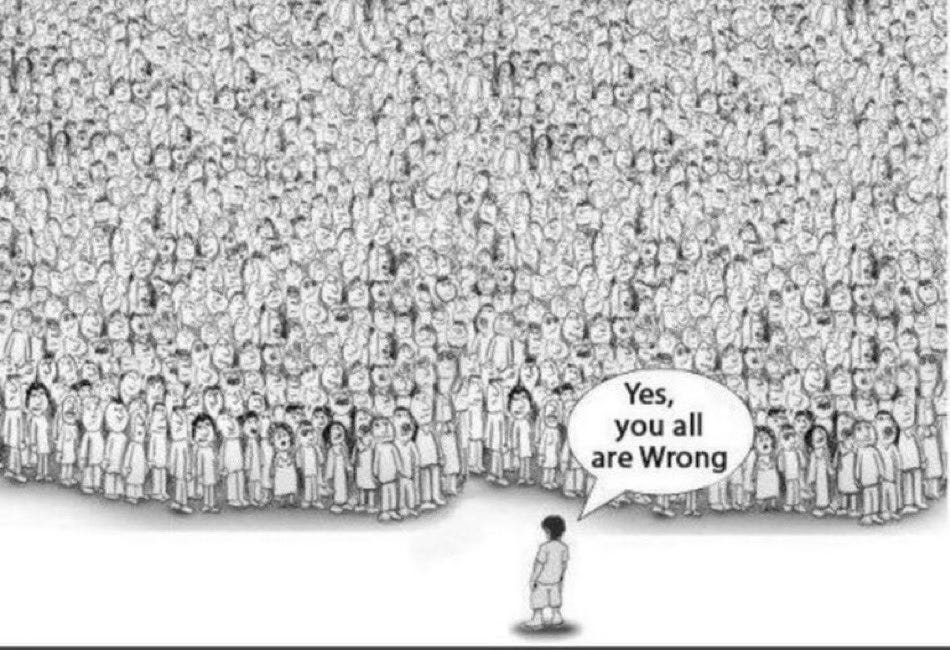

Let me restate – again – that our primary adversaries continue to use political warfare to undermine or dismantle resistance to their aggressive, anti-democratic policies. This is not new; it has been a mainstay of their toolbox since the mid-1940s. Though we initially appreciated the threat and armed according for the war we were in, within a few years, this changed in the face of Russian and Chinese overt military threats. The US relegated defending against their political warfare in favor of a military-first policy. The result has been a Maginot Line of nuclear deterrence and traditional military force readily and increasingly easily bypassed with political warfare since we have blatantly disregarded the flanks. Following decades and decades of decisions made and not made by the Oval Office on down amounts to all but engraved invitations to any adversary to exploit these lateral approaches as we not only failed to defend against these efforts but, in this century especially, failed to impose any meaningful cost resulting from their political warfare.

It is useful to know that Russia and China, among others, would be dumb not to wage political warfare against our interests and those of our democratic allies. Political warfare is inexpensive, especially relative to traditional warfare. Munitions, which include but go well beyond mere “information,” are cheap. The damage to physical infrastructure from political warfare is virtually or completely nil compared to a traditional invasion. If we want to be glib, we can throw in that political warfare is environmentally friendly. Political warfare is tolerant of mistakes and missteps. It allows for multiple and simultaneous, even potentially contradictory, lines of effort along multiple fronts, audiences, and territories. Further, political warfare can result in a deeper and longer-lasting positive result without post-invasion reconstruction, occupation troops, or possibly a directly appointed viceroy, depending on the objective.

Even if you’re not interested in political warfare, political warfare may be interested in you. I wrote “maybe” because a neat trick of political warfare is the ability to bypass or neutralize resistance, like an island-hopping campaign.

What is political warfare?

There is no one clear definition of political warfare. That shouldn’t put you off since the definition of war can be fluid. Some bureaucracies and their cultures object to “warfare” being in the name, leading to the claim they don’t do political warfare because they don’t engage in warfare.1

It’s common to see a reference today to a 1948 memo by George Kennan where he sought to define political warfare:

Political warfare is the logical application of Clausewitz’s doctrine in time of peace. In broadest definition, political warfare is the employment of all the means at a nation's command, short of war, to achieve its national objectives. Such operations are both overt and covert. They range from such overt actions as political alliances, economic measures (as ERP--the Marshall Plan), and “white” propaganda to such covert operations as clandestine support of "friendly" foreign elements, "black" psychological warfare and even encouragement of underground resistance in hostile states…

Understanding the concept of political warfare, we should also recognize that there are two major types of political warfare--one overt and the other covert. Both, from their basic nature, should be directed and coordinated by the Department of State. Overt operations are, of course, the traditional policy activities of any foreign office enjoying positive leadership, whether or not they are recognized as political warfare.2

Two years earlier, in his “Long Telegram,” Kennan used “subterranean” to describe unofficial, deniable, and sometimes overt activities (with covert efforts explicitly and implicitly already included).

Efforts will be made in such countries to disrupt national self confidence, to hamstring measures of national defense, to increase social and industrial unrest, to stimulate all forms of disunity… Where individual governments stand in path of Soviet purposes pressure will be brought for their removal from office.

I could mention NSC 10/2 from 1948, which discusses political warfare, but that’s not helpful here. Reviewing Murray Dyer’s Weapon on the Wall (1959), where he suggests “political communication” as an option to avoid “warfare,” is more helpful, as is James Warburg’s ahead-of-its-time Unwritten Treaty (1946). But here I’ll share a definition from 1954, by Robert Strausz-Hupé (founder of the Foreign Policy Research Institute)3 and Stefan T. Possony, both of whom fall into the far-right anti-Communist bucket:

The purpose of political warfare may be to strengthen some competing groups or to weaken others; to organize forces whose activities can be directed toward desired ends; to support groups for as long as their objectives conform to one's own; and to help fully controlled and semi-controlled groups and personalities to reach positions of power and influence and eventually to take over the government. These methods can range all the way from simple manifestations of sympathy to the financing, organizing, and equipping of political movements, and from personal friendships between statesmen to the infiltration or capture of politically important agencies in the target country and the fomenting of mutinies, civil wars, and revolutions.

Not everyone was on board, though. In 1956, William H. Jackson, who led President Eisenhower’s 1953 Committee on International Information, argued that, after “diplomatic, military, and military means of promoting national objectives,” political warfare “too broad to describe this fourth area of effort.”

This means to me that practically everything, except the use of force, which a government does to attain its national objectives against a potential enemy can be called political warfare. The term is obviously too broad to describe the area of effort remaining after you have dealt with the diplomatic, economic, and military means of promoting national objectives.

A better description – and understanding – of political warfare comes from James Burnham’s 1961 article, “Sticks, Stones & Atoms” (italics in the original):

True political warfare, as understood and practiced by our enemy, is not mere rivalry or competition or conflict of some vague kind. Political warfare is a form of war. It is strategically in nature. Its objective, like that of every other form of war, is to impose one’s own will on the opponent, to destroy the opponent’s will to resist. In simplest terms, it aims to conquer the opponent.

Within the frame of that general objective, the specific objective of each polwar campaign is always defined in terms of power. The purpose in conducting polwar operations is always to increase one’s power in some definite way or to decrease the power of the opponent. In either case, positive or negative, the aim is to alter the power equilibrium in one’s favor.

The power objects may be grandiose—conquest of a nation, disintegration of an empire; or the minor takeover of a trade union, scaring a parliament into defeating a bill, or the sabotage of a factory. But whether big or small, the objective is always power.

My definition of political warfare is derived primarily from Burnham:

Political warfare is the expression of power for hostile intent through discrete, subversive, or overt means, short of open combat, onto another. It is not mere rivalry or competition, it may have strategic or tactical objectives, and it may operate in one or more areas—political, societal, economic, psychological, or other—that are available for exploitation to affect change.

Though specific means of political warfare vary based on time, opportunity, capabilities, and specific objectives, its value and purpose is constant. The target’s media, culture, society, laws, politics, infrastructure, or something else may be targeted and exploited as required or as possible for a desired political effect. Political warfare is about working by, with, or through the local population. What may be considered innocuous engagement in one context may be viewed as political warfare in another. For example, a discussion in Paris about how Americans vote isn’t threatening, though the same discussion in Beijing or Moscow is viewed as subversive by the respective governments.4

The Congressional testimony of

yesterday caused me to share the above. The real difference between yesterday and today is not so much the technology. There were similar concerns about the speed of communications before, though today’s speed means failure to proactively and reactively engage the threat will incur greater pain and higher political and economic costs on the target. No, the real difference between yesterday and today is the willingness and eagerness of persons and organizations in the US to support adversarial objectives and further adversarial political warfare against the US from within the US. I recommend reading and viewing the hearing. Links are on Dr. Snyder’s:I won’t name the bureaucracy (State Department), but this was evident in 1947 regarding critical legislation adapted to respond to Russian political warfare. The bill would become the Smith-Mundt Act, and its purpose as a counter-disinformation, anti-misinformation, and anti-political warfare law has been forgotten, which is ironic and a result and reflection of the current confusion over political warfare and information warfare today. A staff report of a joint and bipartisan Senate and House delegation that traveled across Europe in September and October of 1947 stated the United States Information Service, the mainstay of the informational element authorized by the bill, “is truly the voice of America.” The report listed five objectives it listed of the international information program: (1) explain the United States’s motives; (2) bolster morale and extend hope; (3) give a true picture of American life, methods, and ideals; (4) combat misrepresentation and distortion; and, (5) be a ready instrument of psychological warfare when required. Psychological warfare, a synonym for political warfare at the time, disappeared from the final public version because, as the Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs testified, “in the State Department, we try to avoid psychological warfare.” Interested readers may want to look at Dean Acheson’s autobiography, Present at the Creation, specifically, the chapter titled “The Department Muffs its Intelligence Role,” where he wrote, “Information and public affairs had a better chance and were well served by several devoted assistant secretaries. Eventually they succumbed to the fate of so many operating agencies with which the State Department has had a go, including economic warfare, lend-lease, foreign aid, and technical assistance. In all these cases, either the Department was not imaginative enough to see its opportunity or administratively competent enough to seize it, or the effort became entangled in red tape and stifled by bureaucratic elephantiasis, or conflict with enemies in Congress absorbed all the Department’s energies.”

Kennan’s reference to Clausewitz is likely to this passage from a 1943 translation of the late Prussian’s On War:

War is only a part of political intercourse, therefore by no means an independent thing in itself. We know, of course, that war is only caused through the political intercourse of governments and nations; but in general it is supposed that such intercourse is broken off by war, and that a totally different state of things ensues, subject to no laws but its own. We maintain, on the contrary, that war is nothing but a continuation of political intercourse with an admixture of other means. We say ‘with an admixture of other means,’ in order thereby to maintain at the same time that this political intercourse does not cease through the war itself, is not changed into something quite different, but that. in its essence, it continues to exist, whatever may be the means which it uses, and that the main lines along which the events of the war proceed and to which they are bound are only the general features of policy which run on all through the war until peace takes place. And how can we conceive it to be otherwise? Does the cessation of diplomatic notes stop the political relations between different nations and governments? Is not war merely another kind of writing and language for their thought? It has, to be sure, its own grammar, but not its own logic.

Fun fact: an appointment of Strausz-Hupé as ambassador was blocked by Senator Fulbright because the nominee was too hard on communism. See my post on Fulbright’s role in damaging and undermining our ability to discuss and defend against adversarial political warfare and information warfare here:

Fulbright's "Knee-capping" of US Global Engagement, Part 2

In the spring of 2005, I sat in a university conference room attending a State Department public diplomacy official’s presentation about US public diplomacy. I didn’t know what this “public diplomacy” thing was. I had returned to the university the year before to complete an undergraduate degree in international relations. (I had dropped out in 1992, a …

In Beijing as a Governor on the formerly-named Broadcasting Board of Governors, I met with the second-in-charge of China’s domestic propaganda agency as part of a discussion to get China to uphold its promise to allow a second bureau for Voice of America, which was limited to two journalists and one bureau (compare this to China’s vast footprint across the US, from numbers of employees of Chinese government media operations to their number of offices across the US, to their access to US radio and tv, etc.). As an example of VOA being a news and information outlet, with the latter including information about the US, I offered VOA could have a short segment on how Americans registered to vote. His retort was swift and aggressive: “Don’t tell us how to vote!” He understood.

I am enjoying and learning from your posts about political warfare, a topic that concerns me greatly. As you know, I am also concerned about “netwar” as a spreading reality. John Arquilla and I have tried to call attention to it for years. Just to clarify: Netwar is not so much an alternative to or variant on political warfare, as an updated type of it attuned to the information age.

Plenty of examples exist, and many criss-cross all sorts of domestic, transnational, and foreign boundaries, complicating if not defying efforts to assign a lead agency. I tend to agree that State seems a good option. But if a key concern is the political warfare or netwar currently being waged by militant far-right actors organized into a mesh of domestic, transnational, and foreign networks, I doubt DOS would be (much less want to be) where a lead agency is located.

FWIW, I asked ChatGPT’s Open AI, “What are the differences between "political warfare" and "netwar”?”

It answered okay, but not entirely accurately. It noticed correctly that political warfare tends to be more state-centric and centralized than netwar. But OpenAI over-defined netwar with “the use of networked communications and information technologies …”

As I noted at your prior post, Arquilla’s and my definition defines netwar as an emerging mode of conflict at societal levels involving measures short of traditional war, in which protagonists use network forms of organization and related doctrines, strategies, and technologies attuned to the information age.

As I see matters, classic political warfare is mainly about fights between hierarchical institutions (states, governments, as in Kennan’s time). Netwar is about fights where “Hierarchies have a difficult time fighting networks” and “It takes networks to fight networks.” So far, there’s no USG office or agency for that, though I wish there were (and efforts to combat terrorism and crime have moved in that direction.

Since the related concept “cognitive warfare” has been around for a while, and since I’d wish to advance “noopolitical warfare” as a new concept derived from the ongoing emergence of our world’s long-forecast noosphere (globe-circling “realm of the mind”) atop its geosphere and biosphere, I also asked OpenAI, “What are the differences between "cognitive warfare" and "noopolitical warfare"?

Though I cannot find anyone else using the term “noopolitical warfare” yet, OpenAI didn’t blink, and answered correctly that the terms are almost interchangeable, then added: “In summary, while both cognitive warfare and noopolitical warfare involve the use of information and psychological tactics, cognitive warfare tends to focus more broadly on influencing behavior and perceptions, while noopolitical warfare specifically emphasizes the strategic competition over ideas and knowledge.” Pretty good, esp. the “strategic” aspect, and I’m relieved it did not question the latter concept.

Sir, I’ve read with much interest your articles and shared them with colleagues. I keep coming back to the same conclusion about political warfare and what agency should be responsible for U.S. efforts, namely the State Department. When the OSS was disbanded, the subsequent missions were farmed out to the CIA, State and military. INR at State, in my opinion should be the lead of our intelligence understanding of political warfare and the conduit to decision makers. This would of course require a massive investment at State and a mission update, which I’m sure will not be easy to do. Curious to your thoughts on what agency should lead our efforts.

Thank you for your continuous efforts to bring this to the forefront of national conversation.