R changes coming?

Looking into the overdue nomination for Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy

The Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs, known as “R” in the State Department’s shorthand, was established in 1999 as a functional replacement for the Director of the simultaneously abolished US Information Agency. Since October 1, 1999, when the first R took office, the office has been vacant nearly half the time. This remarkable statistic only partially reveals the lack of importance of this position across successive administrations. Another measure, albeit subjective, is looking at the highlighted qualifications of the people confirmed into this office and how they were supported, held accountable, or ignored by the Secretary of State and President. With acting officials holding this office 37% of the Bush administration, 22% of the Obama administration, 93% of the Trump administration, and 100% of the Biden administration, another avenue of analysis is comparing the qualifications of the people delegated the authorities of R to the confirmed appointments.

Government agencies abhor leadership vacuums, and the absence of a confirmed R further marginalized an already ill-defined, under-appreciated, and poorly-resourced element of national security and foreign policy within the State Department, the National Security Council, inter-agency partners, and Congress. Considering how this office was and remains positioned as the government’s chief international information and engagement officer, it is remarkable this position is so ignored and sidelined despite repeated rhetoric of being in an “information war” and a “battle for hearts and minds” (two terms that are as problematic and misleading as the term “public diplomacy”) for the past two decades. Consider the many articles over the years calling for a “return” of USIA or some other central hub and the deafening absence of even a mention of R. Consider, too, the creation of the Global Engagement Center and its predecessor and whether the role of R was anything more than a matter of bureaucratic convenience.

One of the best analyses of this situation I’ve read is from May 2021 and by Uliana Artamonova: “Faceless Leadership of American Public Diplomacy: HR Crisis in the Post-Bipolar Era” (this PDF is stored on mountainrunner.us). Artamonova, a junior research fellow at IMEMO, shared her article with me in March 2022. From her abstract:

Comparison demonstrates a considerable change of patterns: since 1999 persons in charge of American public diplomacy have been changing more often and the position itself stayed vacant longer then it did in 20th century. There have been many acting nominees during the past decade whereas in the time of USIA there has been none. In addition, article studies characteristics of directors of USIA and of Under Secretaries of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. Analysis of education, professional background, personal relationship with the president (or lack of thereof) demonstrated that standards for candidates for the position of Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs are significantly lower than the ones that were applied to candidates for the directorship of the USIA.

I recommend her paper to anyone truly interested in this topic, especially if you’ve read even this far. Our willful blindness to appreciating the mutual dependency between information and foreign policy is astounding, which Artamonova’s paper shines a light on.

Last week, the President announced his intent to nominate Elizabeth Allen as the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy. An “intent” means the nomination hasn’t happened in that the paperwork has yet to be sent to the Senate.

In 2021, the Senate confirmed Allen was appointed the Assistant Secretary of State for Global Public Affairs. She held that position from September 2021 until April 4, 2022, then she moved into the role of acting Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. The Assistant Secretary for Global Public Affairs (“GPA”) is notionally under R, but in practical terms, they functioned more like peers.

Before Allen’s move to be the acting R, Jennifer Hall Godfrey held the position. Godfrey is a career Foreign Service Officer in the public diplomacy “cone” (“of the public diplomacy cone” sounds better to me) and was the acting R for 435 days beginning with the start of the administration. By the way, the Assistant Secretary for Global Affairs, the position Allen vacated to take on the R job, is temporarily filled by (i.e., another “acting”) another career public diplomacy FSO, Elizabeth Trudeau.

It is doubtful there was ever a serious consideration of nominating an FSO to this job. The Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy is unlike the Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, which has historically been considered the most senior position a current FSO can reach. This was not the case with USIA, which Artomonova noted included two career Foreign Service Officers serving as Director. One was George V. Allen, who served previously as the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs when this position had a larger portfolio with more authorities than the yet-to-be-established USIA, and the other was John Reinhardt.

In the 23+ years the position has existed, nine people have been confirmed by the Senate to be the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy, compared to 14 USIA Directors across 46 years. The under secretaries served, on average, less than 19 months in office (the median tenure is about 17 months). The tenure of an R is on par with that of a President’s chief of staff, a position known to have a short shelf life. However, while this CoS position gets filled, the R job is left “empty.” Excluding the Trump administration, which had an R for a mere 100 days, and the Biden administration, which is yet to have a confirmed R, the average time between the departure of an incumbent and the entrance of the successor was over seven months, with the median at eight months. Put another way, between October 1, 1999, and the end of the Obama administration on January 20, 2017, the office was vacant 28% of the time. If we include the Trump and Biden administrations, this office has been 45% of the time since it was established.

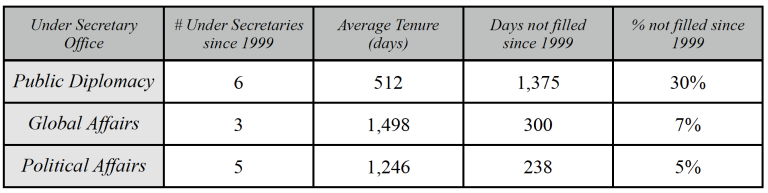

In December 2011, in a report for the Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy, an entity which, for the past decade, has been strangely silent on the ramifications of the lack of a confirmed appointment to this under secretary position, as the commission’s executive director, I compared the gaps between the appointments of R with the Under Secretaries for Political Affairs and the Under Secretary for (the then-named) Democracy and Global Affairs. The differences were stark then and likely more so now. (With regard to Political Affairs, there have been three under secretaries, bringing the total number to 8 compared to R’s 9, and only one “acting” who served about three months.)

A different approach in considering the perceived value of this position to an administration is the time until the first confirmation. President Bush’s first R was confirmed 254 days into his administration, and Obama’s first R took office 124 days in. Trump’s R started 316 days into the administration. We are now 737 days after January 20, 2021, and counting.

Does Allen’s nomination indicate some kind of shift? Maybe, or maybe not.

My first inclination is – and this is not a comment on Allen – this nomination is a matter of convenience. It does not reflect a change in the general lack of appreciation of the office’s potential value. There were rumors about a nominee for R way back when Allen was nominated and confirmed to be the Assistant Secretary for GPA. I don’t know if the rumors or aspirational reflections of probative conversations were true. Still, the nominally subordinate assistant secretary's appointment before the boss – R – was announced reflected either a continuing disconnect between the two or the prioritization of GPA over R, or both. History shows the two positions followed separate tracks to their respective appointments, with not having a meaningful, if any, say in the selection of the assistant secretary. There is no evidence to suggest any difference in 2021.

The question “why now” is probably better asked as “why not now?” There were two reasons not to make a nomination to date. The first is a nomination is pending. That does not seem to be the case. It is unlikely a serious candidate for this position is willing to step in without the clear support of the Secretary of State and the White House to fix decades of neglect and marginalization. Any other candidate seeking this position without these assurances is either short-sighted or setting themselves up for failure for the sake of having “former Under Secretary of State” and “Ambassador” in their future biographies.

The second reason to leave this office vacant is a major restructuring in the works, possibly abolishing this vestigial remnant. That may be a good thing, as would be abolishing the term “public diplomacy,” a term intentionally crafted to segregate rather than integrate methods and outcomes.

What about the title used in the intent to nominate announcement?

The announcement used “Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy” and not “Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs.” This may be meaningful, or it may not be.

Let’s step back in time to look at this and look at why the term public diplomacy exists. Many folks, including (especially?) public diplomacy scholars, neglect to notice that “public affairs” was fit for purpose for over twenty years before the term “public diplomacy” was co-opted and introduced as an umbrella term for the activities of a specific agency. Established as the Assistant Secretary of Public and Cultural Relations in December 1944, with the Office of Public Affairs below it, it was renamed the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs in 1946. “Cultural Relations,” then a concept broader than it is conceived today, became a lightning rod. See, for example, the Introduction by Archibald MacLeish, the first Assistant Secretary for Public and Cultural Relations, to The Cultural Approach by Ruth Emily McMurry and Muna Lee (The University of North Carolina Press, 1947): “The old adage about giving a dog a bad name applies with a peculiar reverse twist to the subject of this book. ‘Cultural Relations’ is not a bad name in itself; on the contrary, it has all the attributes of gentility and virtue. It is merely a bad name for the thing it describes.”

Since 1946, the informational and cultural aspects of international engagement were under the umbrella of public affairs. In 1953, when USIA was created, public affairs remained adequate. Over a decade later, a center at Tufts University opted for “public diplomacy,” a term then frequently used in the press to describe the use of the press as bullhorns by diplomats. The term did not gain momentum – even the Tufts center rarely used the term – until Rep. Dante Fascell, Democrat from Florida, chair of the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, issued a report on “The Future of United States Public Diplomacy,” based on a one-day symposium “of the US image abroad, the relevance of the image to US leadership of the free world, and the new directions to be pursued in the age of public diplomacy,” in December 1968. In 1977, the Advisory Commission on Information and the Advisory Commission on Educational Exchange, both established by the Smith-Mundt Act (added to the “Mundt bill” by then-Congressman Everett Dirksen), were merged and renamed the Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy.

This tells us why the term is so nebulous today: it was adopted to apply to an agency – USIA – and not as a label for means, intentions, or outcomes. Today, only some offices “do” public diplomacy while others, even if conducting identical programs, don’t because they have ancestral (or obvious) lines back to USIA. Some might argue a direct link to the Smith-Mundt Act is necessary for “public diplomacy,” but this is demonstrably false considering the breadth of office and activities that do not derive their authorities from the Smith-Mundt Act, most of which were workarounds because of turf issues, problems with R, and the label “public diplomacy,” including the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, the Office of Global Partnerships, the Global Engagement Center, any informational activity of the Defense Department, etc.

With “public diplomacy” as a term applying to USIA activities by Washington, observers, and academics, how did it get to the State Department?

In the 1997 agreement where Congress established a position in the State Department to functionally replace the Director of the USIA, the position’s title was the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy. USIA had been, after all, in charge of “public diplomacy,” and this new position would manage the bulk of USIA’s operations, most of which were placed in the brand-new Bureau of International Information Programs. USIA’s radio operations, previously placed under an oversight board established in 1994, became an independent federal agency, the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). IIP took on USIA’s vast library network abroad, its global printing and distribution network, its media production capabilities, its newsroom, its speaker tours, and many other methods of direct contact in the “last three feet” across the globe. Through IIP, the under secretary could continue to support the public affairs sections at US embassies and consulates abroad. For reasons I have not uncovered, the Clinton administration decided the new position would be the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs instead. Perhaps this was a hopeful effort to bridge the gap between foreign and domestic, a gap created by the creation of USIA, amplified by Senator J. William Fulbright’s attacks on USIA, Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberty in the 1960s, and subsequently ossified by Fulbright’s 1972 amendment to the Smith-Mundt Act. The separation of foreign from domestic information activities, later referred to as a so-called “firewall,” ran counter to the State Department’s operating concept behind the Assistant Secretary for Public and Cultural Relations and counter to the intentions of Congress in the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948. The modern narrative of the Smith-Mundt Act as an “anti-propaganda” began with Fulbright – “a relic of the Second Zulu War” – and cemented by Senator Edward Zorinsky’s amendment in 1985 closed “loopholes” in Fulbright’s amendment. Consider the reality that information used abroad under the public diplomacy umbrella could only be available to Americans if “scrubbed” through the Assistant Secretary of Public Affairs office.

It is possible “Under Secretary of Public Diplomacy” reflects an intentional bifurcation of foreign from the domestic, an idea that implicitly goes along with the Fulbrightian argument – selective, näive, unilaterally disarming as it is – the government’s voice is inherently tainted. The things said abroad authorized by the Smith-Mundt Act are unfit for Americans to see, hear, or know about, unless “scrubbed” by Main State’s public affairs, which is not the same as public affairs at posts abroad because the latter – the uninitiated need to follow this carefully – despite the title as public affairs officers working in a public affairs section are public diplomacy agents. Besides reducing necessary oversight, this restricts awareness and support of the activities, whether the view is from Congress, the public, the press, or even across the State Department and inter-agency partners. Left out of the Fulbright biographies – and articles that falsely claim Fulbright’s amendment was a techinical fix to align the legislation to the original intent – is Fulbright claimed the Soviet Union and communism were not a threat to the security of the US. Also left out was his changing the authorization of USIA to a single year, which was soon reversed. I suspect this was raised, though probably in simpler terms like “PD can’t be seen by Americans", and thus only part of the answer.

The title may reflect the change in the structure below R. The Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP), the largest rump of USIA when excluding the capital costs of the BBG, was selectively folded into the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs to create the Bureau of Global Public Affairs. The Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Global Public Affairs is just weird. What, after all, is Global Public Affairs but public diplomacy? So why not Under Secretary of Global Public Affairs? Well, that gets confusing quickly, plus, there are probably some, like the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), that, in the Obama administration, began objecting to the idea it was subordinate to R, who do not want to be under “Global Public Affairs.” It’s a mess, and mostly because of a darn term that continues to segregate rather than integrate.

Ultimately, I am not reading anything into the intent to nominate announcement. It is not binding, and the State Department website doesn’t show a change in the “full name” of R. I think it’s just shorthand for a position that matters little in the scheme of things and that Allen is getting pat on the back in the form of an under secretary title that also comes with an Ambassadorship. The appointment will also reduce some heat, if any is coming, as to why the administration has yet to appoint an R since we’re in a so-called “information war.”

Obvious problems with the new Bureau of Global Public Affairs and the distinction between foreign and domestic exist. These are likely amplified by the accepted wisdom of what the Smith-Mundt Act intended to do and the changes from and intentions of the Modernization Act of 2012 (for those unaware, State made its preferences known in the language and did not seek to loosen things up).

By the way, under secretaries at the State Department were given single-letter designations, like P and J, though J is now G. This under secretary got the “R” designation because, claimed a State Department official tasked with the job in a conversation with me years ago, because it was the best of the available letters. That official, Rick Ruth, stood by that story and told me it had nothing to do with his name. Rick, if you’re reading this and wish to correct the story you told me in your office a long time ago…

More interesting than the shortened title in the intent to nominate is the rumor the Global Engagement Center will become a bureau. I’ve long argued GEC was established as a kind of USIA on the cheap, though most likely unwittingly. Creating GEC was far easier than fixing and adapting IIP. GEC exists below R and relies on R to clear its paperwork, including expenses. It has to exist somewhere, after all.

Would anything change if GEC becomes a bureau? Would the Special Envoy and Coordinator, the title of GEC’s chief, become an assistant secretary? Not necessarily. IIP was a bureau, and it had been led by a Coordinator. In 2008, Jim Glassman, then R, was able to get authorization for IIP to be led by an assistant secretary. He was unable to fill the seat, and his successor, Judith McHale, opted for the direct-hire route of the Coordinator title instead of the Senate-confirmed Assistant Secretary (whether this for short-term expediency or because there were questions the person was not confirmable is moot at this point, ultimately they did massive damage to the bureau), allowing the department to use the allotted assistant secretary elsewhere.

Would GEC be renamed GEB (Global Engagement Bureau), BGE (Bureau of Global Engagement), or – wait for it – the Bureau of International Information Programs? Regardless, I’d wager the GEC bureau would take on some of the responsibilities of Global Public Affairs formerly found in the stand-alone IIP rather than fix the Fulbright-Zorinsky perversions to the Smith-Mundt Act. Such a change might reinvigorate R, but what of ECA and the relationship of R with the regional bureaus and posts? Will a revised GEC support the posts as IIP had but subsequently failed to do? Will a revised GEC support the interagency as IIP should have but often refused to do (cf. SETimes dot com and the like and SASC working with DOD and BBG to trial run a better solution, something I helped negotiate)?

I don’t know what will happen. Frankly, I’m pessimistic there will be any substantial change. I hope to be proven wrong, which I’ll happily own, but the indications are in my favor.

I’d like to hear your thoughts directly or through the comments.

The cover image used for this post is partially obscured but probably of interest to some readers, especially those who got down here to the end. Here is the whole image: