There was a legal path to closing USAGM

The way the networks were suddenly shuttered reveals bad faith and an amateurish approach to US foreign policy

Yesterday afternoon, I submitted an op-ed to The Hill on the shuttering of the US Agency for Global Media and its networks. As I am writing this, I received word that they’ll publish it. I’ll add that link here and share it separately when it’s online. [My oped is now published.]

There is a paragraph in that op-ed stating the administration could have stopped USAGM’s operations legally. The haste and disregard for the law displayed in the executive order that “eliminates non-statutory functions and reduces statutory functions of unnecessary governmental entities to what is required by law” is revealed not just by the absence of law but also by the fact that the EO ends with an incomplete sentence.

This EO was aimed at several other entities, but I won’t get into the issues surrounding them for the simple reason that I don’t know enough about the relevant statutes and history of those organizations. I do, however, have a deep understanding of the applicable statutes to USAGM and its parts.

The overriding legislation here is the Smith-Mundt Act.1 The bill South Dakota Republican Rep. Karl E. Mundt introduced on January 24, 1945, was to authorize exchanging teachers-in-training between the American republics (how we used to refer to the countries across South and Central America). Archibald MacLeish, the Assistant Secretary of State for Public and Cultural Relations, was deeply interested in the bill after his good friend, Dean Acheson, forwarded it to him. In August, President Truman issued an executive order to close the Office of War Information, which had been established through the same means, and send the international information programs of OWI and the Office of Inter-American Affairs to the State Department. The President gave the department until the end of the year to develop recommendations on how the information programs should be structured and operated in the government.

Earlier, the President asked OWI for its recommendations on the “liquidation” of the office, specifically where the operations that should continue should reside and why. That memo was delivered two weeks before the President’s executive order. OWI’s advice, in turn, copied, in letter and spirit, from a 241-page report MacLeish commissioned an roving consultant to the department before Mundt’s bill and completed in July. This analysis incorporated the views of OWI and many other agencies and groups across and outside the government. Truman’s decision was based on, and virtually mirrored, the recommendations OWI gave the President two weeks earlier, which largely came from the report MacLeish had commissioned.

The first line of the report set the tone: “The adequacy with which the United States as a society is portrayed to the other peoples of the world is a matter of concern to the American people and their Government.” The issue wasn’t a matter of cultural exchange but addressing the disinformation, misinformation, and information gaps that interfered with US policy, security, and trade. The second paragraph of the report stated this clearly:

International information activities are integral to the conduct of foreign policy. The object of such activities is, first, to see that the context of knowledge among other peoples about the United States is full and fair, not meager and distorted and, second, to see that the policies which directly affect other peoples are presented abroad with enough detail as well as background to make them understandable.

The report MacLeish commissioned stated this while offering four future organizational scenarios to consider. OWI, agreeing with the spirit of the report they contributed to, advised the President regarding the “General information service by the government to the rest of the world… We emphatically believe that there should be such a service and that it should be under State Department jurisdiction.”

However, the advice was very different regarding the radio operation, often called the Voice of America.2 This was a distinctly different activity than the other international information programs sent to the State Department. The OWI recommendation, also reflecting the spirit of the earlier report, said the radio operation, including the transmitters and relay stations overseas, was “These facilities should be held intact and operation continued under the State Department until the US Government decides on an eventual disposition which will be in the best interests of the nation. We suggest that steps be taken immediately to have a presidential commission or a congressional committee study the problem and make recommendations.”

The “Facilitative and Supplementary Nature of Government Information Activities,” as the first heading of the State Department report read, was deeply embedded in the thinking and consideration of how the broad information programs, including the radio operation, would work.

(1) The portrayal of the United States must be accomplished substantially by the normal currents of private interchange through the media of the printing press, radio, camera and screen, and others, and the complex institutions that rise spontaneously about them.

(2) The role of the Government is important but it is facilitative and supplementary. Some of the clements are facilitative, like governmental policies which may promote the cheapness, equality, speed, and universality of press communications. Some of the elements are supplementary in the sense that they must be conducted by the Government, or with its support, if they are to be conducted at all (for example, fast transmission abroad of full texts of important American speeches).

The last parenthetical is important. Recently, VOA simulcast and translated President Trump’s Joint Address to Congress in Russian, Ukrainian, Farsi, and several other languages, providing direct and immediate access from 1945 to the present, or at least until the end of last week.

The phrase “facilitative and supplementary” quickly became a figurative drum constantly beating in the background in discussions about the broad information program, including the US Information Service and VOA.

Before six days of hearings in mid-October, Mundt’s bill, known since July as the Bloom bill, had been expanded to include more exchanges than only teachers-in-training and had quickly inserted a few words about the information program. Questions about the need and scope of information programs dominated the hearing. The State Department expressed hope and the expectation that private agencies would eventually inform people abroad. As William Benton, MacLeish’s successor, testified in October 1945:

The Government’s role here is facilitative and supplementary. Its first job is to be helpful to the private agencies engaged in international exchange of information, skill and art, and to the tens of thousands of private individuals going abroad who act as our cultural ambassadors. The second job of Govemment—the supplementary job—is to help present a truer picture of American life and American policy in those areas important to our policy where private interchange is inadequate, or where misunderstandings or misapprehensions exist about the United States

Congress agreed. The bill discussed in October was modified in November. This bill had always been an amendment to existing authorities. The precise extent and limit of the authorities to be amended were unclear to everyone, so in December, the bill was rewritten as a stand-alone bill. The “facilitative and supplementary” element was embedded in the December 1945 authorization for the Secretary of State, “when he finds it appropriate, to provide for the preparation, and dissemination abroad, of information about the United States, its people, and its policies, through press, publications, radio, motion picture, and other information media.”3

Though the expansion was explicit, a contraction or shifting of services was merely implicit. Concerning the radio operation, Congress and the State Department wanted the explicit authority to reduce this programming as conditions changed.

The bill passed the House comfortably, but it was sent to the Senate just weeks before the end of the 79th Congress in July 1946. Some Members did not feel the bill was not wholly necessary. State pointed out that without the Bloom bill, it lacked, for example, the ability to detail a government official outside of the Western Hemisphere, raising the concern that an agricultural mission sent mission “to the Arab countries” under emergency funds will have to be recalled. Further, some twenty-six other government agencies were relying on authorities in the pending Bloom bill, including the Civil Aeronautics Administration, which was unable to cooperate with Canada to “erect a radio beam in Michigan to guide Canadian planes flying the Great Lakes, a beacon Canada offered to pay for. Then there was the Senate’s Republican leadership, which viewed the bill as partisan and blocked further consideration after the Senate Foreign Relations Committee recommended: “Do Pass.” As a result, we don’t call it the Bloom Act of 1946.

The State Department still needed the authorities. In April 1947, they sent a slightly revised version of the Bloom bill to the House and Senate. Mundt picked it up in the House and H. Alexander Smith, a Republican from New Jersey.

However, despite the critical need for those authorities, the State Department’s top priority was not the Bloom bill and its authorities. The more critical effort was privatizing the Voice of America operation, which they began pursuing in November 1945. Smith, however, would not cosponsor the bill if the radio was separated from the government. He said VOA belonged “right in the lap of the Secretary of State.”

In the bill the State Department sent to Congress in April and Mundt introduced in May was that language that in “authorizing international information activities under this Act, it is the sense of the Congress (1) that the Secretary shall encourage and facilitate by appropriate means the dissemination abroad of information about tile United States by private American Individuals and agencies, shall supplement such private information dissemination where necessary, and shall reduce such Government information activities whenever corresponding private Information dissemination is found to be adequate…”

The drumbeat of “facilitate” and “supplement” continued, as did the emphasis on encouraging private agencies to work abroad. There was new language, though, to direct (“shall”) the reduction of the “information activities whenever corresponding private Information dissemination is found to be adequate.” This language was later elevated, becoming Sec. 502 of the Smith-Mundt Act, “In authorizing international information activities under this Act, it is the sense of the Congress (1) that the Secretary shall reduce such Government information activities whenever corresponding private information dissemination is found to be adequate.” Today, this language is found in 22 USC 1462 as a non-compete and a sunset clause.

There were discussions about what “adequate” meant, like in the Senate during Executive Session meetings in July 1947. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., asked, “I want to know whether this word ‘adequate’ is a strong enough word, whether you want to say ‘is found to be in harmony with American foreign policy.’ It is not a question of whether… they have the signal strong enough” to reach the destination.” Senator Carl Hatch replied, “We so construed that it was adequate.”

Last week, there was no finding that private information dissemination activities were deemed adequate or even a pretense of such. The administration quite easily could have done with it while arguing what “adequate” meant. They did not because the shutdown was not performed in good faith.

USAGM and its networks need to be reformed. I won’t argue that; in fact, I’ll be the first to raise reasons they must be reformed and potential pathways to increase relevance, efficiency, and impact.

In July 1947, the former chief of the State Department’s Division of Cultural Cooperation and then President of the New School for Social Research sent Mundt a note reflecting the arguments against the Smith-Mundt bill that seems fitting to share today.

It is inconceivable to me how some citizens and some members of Congress can think of throttling the informational and cultural exchanges of the Department of State at a moment when we ought to be making our maximum effort to represent ourselves in an honest and good light. Imagine a great corporation confronted with a somewhat similar situation to that now confronted by the greatest of all corporations the United States of America — eliminating its public relations budget completely. What we need in the United States Government is a business-like method, and your bill is in the best of that tradition.

One last comment: While VOA and the Office of Cuba Broadcasting have little recourse, the grantees, Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty, Radio Free Asia, and the Middle East Broadcasting Networks, do. Each operates on a grant from USAGM, hence the term “grantee,” and exists outside the government. They can also accept funding from outside the US government. RFE/RL had, last I checked (though that was many years ago, a foundation to receive funds. RFE/RL’s building in Prague, which is no longer owned by RFE/RL (that is a corruption story), is leased by RFE/RL and not USAGM. We’ll see what happens. The RFE/RL board chair said they are exploring the way forward. Good luck to them.

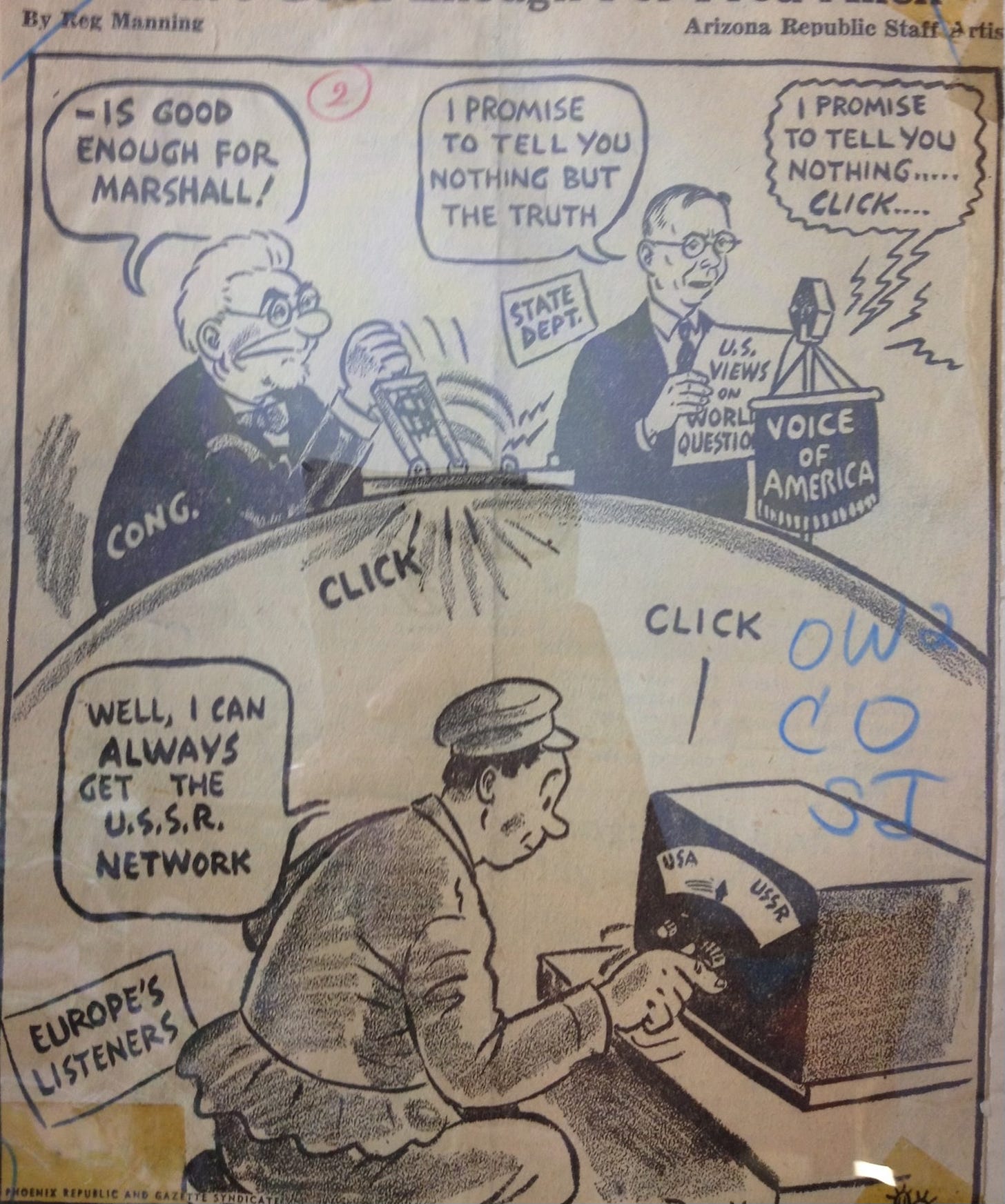

I’ll end with a cartoon from 1947. Though the cartoon shows Congress flipping the switch off in the cartoon, it fits. The silence left will be filled by Russia, China, and others who cheer the disappearance of the journalism that exposed their disinformation and political warfare.

Or should it be “underlying legislation”? I guess it’s a matter of perspective to go with foundational (underlying) or supreme (overriding).

The broadcasts were called Voice of America. However, the name did not apply to the whole radio operation until 1946.

It is important to know that the “dissemination abroad” language was an explicit authority granted and not a restriction imposed. There was a lack of clarity on where the department’s information activities could reach. Was it just the Americas, or was it legal to reach other countries? “Abroad” was a blanket permission that conveniently required few words. In deliberations later, Congress sought to remove the phrase because they thought it was unnecessarily wordy, but the discussion moved on when the department and other members recalled the purpose of the text.

Grahame, shortwave is useful and digital shortwave is cool, but the audience share is relatively small, smaller when you look at who you really want to reach if you need to prioritize. When I was on the BBG board, I chaired a committee looking into the agency's need and utility of shortwave. That report was called "To be where the audience is" and it's still on the USAGM website: https://www.usagm.gov/2014/08/01/to-be-where-the-audience-is-report-of-the-special-committee-on-the-future-of-shortwave-broadcasting/

I don't know enough about the userbase for shortwave in, say, Australia, but, in general, shortwave has been a declining medium with lower ROI. Your paranthetical acknowledges that reality.

What you describe with regard to the HF spectrum and China is opportunism made possible when one understands the potential value in its use. Whether they'll use that spectrum for transmitting programs or for other purposes, I don't know.

About RFE/RL over the air broadcasts, I think it's likely some will be abandoned for financial reasons. It is possible that RFE/RL picks up other frequencies, say the more limited MW, through local relationships and tighter relations with European governments as the network re-establishes itself. (Related but separate: I wonder if we'll see a corporate restructuring to further severe the connection to the US based on some concept of self-protection.)

Matt, what do you think China is doing with all of the SW frequencies they occupy? In Australia Chinese broadcasts are wall-to-wall. Do they want to assert "ownership" of a kind over the HF broadcast spectrum? (Chinese-Australian people I know are unaware of SW let alone the Chinese language services of CNBC et al. They get their news from apps, not radio of any kind). When Radio Australia vacated the HF spectrum I understand that China took those frequencies over rather quickly. Is this what will happen with the VOA RFE frequencies?