Tactical Solutions Will Not Fix a Strategic Defect

A shallow understanding of the problem means focusing on symptoms not the root cause

A colleague recently referred me to the following passage in the recent Commission on the National Defense Strategy report and asked, “What would you do?”:

Implementing the [National Defense Strategy] requires a skilled, global, rapid communication and messaging ability to compete with the mis- and disinformation machines supported by Russia, China, and others—including even the Houthis, who have managed to turn attacks on trade and free navigation into a Middle East cause célèbre. Both State, primarily through the Global Engagement Center, and DoD need to rebuild the kind of ability provided by the U.S. Information Agency and the Active Measures Working Group during the Cold War to communicate and counter U.S. adversaries’ pervasive messaging and propaganda. This requires the ability and authority to provide and respond to content at the speed of the news and social media cycle.

I wouldn’t answer the question, however, because the report presents a flawed understanding of the historical and contemporary context of our international information operations’ organizational structure and practices. Moreover, the authors mistakenly suggest that policy and information are independent, emphasize reactive responses rather than proactive integration, and undervalue the impact of presidents and cabinet secretaries on our current capabilities and potential reforms. Through this glaring omission, the authors absolve the offices most responsible for the current condition—the Oval Office and the President’s direct reports, from the cabinet to the national security staff—and hope a tactical effort will fix a strategic defect.

The report implies that we “got it right” with the US Information Agency (USIA), an organization created to segregate the informational element from policy, a separation that was premised on authorities it was never granted, and, within four years, began calls for major reforms or reintegrating the operation into the State Department.1 The Active Measuring Working Group (AMWG) was created because USIA did not, institionally, do what the report’s authors think it did. As a history on AMWG notes, the “inclination to challenge Soviet disinformation declined over the 1960s until, by 1975, there was no organized, overt effort to expose Soviet disinformation at all.” And then there is the Global Engagement Center (GEC), created to both compensate for years of absent leadership at the State Department and to make something new rather than fix what is there.

The report’s entire paragraph on information (114 words) is faulty, unhelpful, and useless concerning moving toward a practical and enduring solution. Ignoring the rest of their report, here is my quick and dirty replacement (118 words):

Implementing the NDS requires a comprehensive approach of integrating the informational elements of policy with the making and conduct of policy. Informational efforts and policies must be mutually reinforcing to the maximal extent feasible. This posture begins with the President and requires each cabinet secretary, and their subordinates, to instill and support the necessary operating principles within their organizations. It is not likely more authorities are necessary, but clarification of authorities is required. Abilities and speed will follow with appropriate empowerment, education, and encouragement to act within and across organizations provided appropriate support and protection is provided by leadership. We lack the necessary dynamism because we have more fear of the errant message than of the errant munition.

If the report had something similar to my paragraph, I would quickly answer my colleague’s question. But it didn’t, so let me explain my criticism before answering.

A Story Hiding in Plain Sight

Nearly twenty-three years have passed since Richard Holbrooke asked, “How can a man in a cave outcommunicate the world’s leading communications society?” His complaint highlighted a critical lack of leadership, a persistent issue that worsened after decades of inattention. While it’s clear that poor leadership led to our current situation, many mistakenly believe that simply restructuring will magically resolve the problem. In reality, leadership is the driving force behind an organization’s success, and it is leadership that enables and supports the structure, not the other way around.

Holbrooke condemned the government’s cumbersome systems for supporting foreign policy through “public diplomacy, or public affairs, or psychological warfare, or—if you really want to be blunt—propaganda.” Though written immediately after the September 11th attacks, his critique remains relevant.

Despite our nation’s overwhelming supremacy in modern communications, our government primarily communicates with the Muslim world through pathetically outdated or inappropriate technologies and a bureaucratic structure that is not remotely up to the task. The senior official in Washington working on these issues is the under secretary for public diplomacy and public affairs, now Charlotte Beers, a successful advertising executive with no prior government or foreign policy experience. The people in the structure she inherited (she has been in office just a few weeks) are the vestiges of the U.S. Information Agency, a Cold War agency that was folded into the State Department in 1998-1999. Its personnel have limited background or experience for the issues they must now address.

Holbrooke correctly identified the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs as the government’s chief international information operations officer. And note that he did not call for resurrecting an agency disbanded only two years earlier. Positioned within the foreign policy machinery, the undersecretary was the conceptual and operational successor to the USIA Director.2 Separating USIA’s broadcast operations, less than 30% of the agency’s staff, into an independent agency was irrelevant.3

The Commission’s neglect of the undersecretary underscores their focus on organizational structures rather than leadership.4 Given the office’s history since 2001, it is not surprising it was overlooked. However, its status should have prompted greater scrutiny from the Commission and other observers.

Holbrooke’s critique that the officeholder lacked government or foreign policy experience has been a recurring issue. The limited view of the office’s potential led to low hiring standards, apathy in filling the position, and marginalization and ineffectiveness of the broader functions. Since its creation in 1999, the Office of the Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs has been vacant for nearly half its existence.5 Successive administrations consistently failed to fill this key leadership role, reflecting a disregard for its importance in proactively shaping public perceptions and understanding and advancing foreign policy goals and in leading reactionary efforts to counter and mitigate adversarial disinformation and incidental misinformation. The prolonged vacancy of a senior position and a lack of engagement from leadership above and adjacent can and does significantly damage an organization’s reputation, relevance, and effectiveness.6

Holbrooke recognized the undersecretary’s office could have been crucial in international communication efforts, from addressing disinformation, misinformation, and information gaps. The Bureau of International Information Programs (IIP) inherited the largest element of USIA and reported directly to the undersecretary. It was responsible for a wide range of activities, including on-the-ground operations worldwide, printed materials, direct digital initiatives, and supporting broad State Department requirements and interagency requests. However, due to feckless leadership, IIP declined, was bypassed, and ultimately dismantled.7

Workarounds by the White House and the State Department led to a series of short-lived organizations notionally below the undersecretary to compensate for a variety of shortcomings, including the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism (CSCC), the Global Strategic Engagement Center (GSEC), and the Global Engagement Center.8 Between Holbrooke’s public question and CSCC, there were countless other efforts: Strategic Communication Policy Coordination Committee (PCC, September 2002), co-chaired by the National Security Council and the State Department; the PCC set up an interagency Strategic Communications Fusion Team (December 2002); then there was the White House’s Office of Global Communications (OGC, January 2003); and so on. Some may recall Interagency Policy Committees (IPCs), like the Strategic Communication IPC, or the essentially meaningless National Framework for Strategic Communication (March 2010). Experiments were replaced or whithered away from a severe lack of interest in the informational side of policy from above and allowing bureaucracies to return to their comfort zones.9 The President and the cabinet must be on the same page and maintain pressure to get it right, but they haven’t. Putting people in a room and hoping for the best isn’t leadership or strategy.

Interested readers should look at a report examining the different approaches to the undersecretary and the USIA Director. Uliana Artamonova, a research fellow at Russia’s Institute of World Economy and International Relations, shared her report with me in March 2022. This is an excerpt from “Faceless Leadership of American Public Diplomacy: HR Crisis in the Post-Bipolar Era” (this link points to a scrubbed PDF stored at my old blog, mountainrunner.us):

Comparison demonstrates a considerable change of patterns: since 1999 persons in charge of American public diplomacy have been changing more often and the position itself stayed vacant longer then it did in 20th century. There have been many acting nominees during the past decade whereas in the time of USIA there has been none. In addition, [this] article studies [the] characteristics of directors of USIA and of Under Secretaries of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs. Analysis of education, professional background, personal relationship with the president (or lack of thereof) demonstrated that standards for candidates for the position of Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs are significantly lower than the ones that were applied to candidates for the directorship of the USIA.

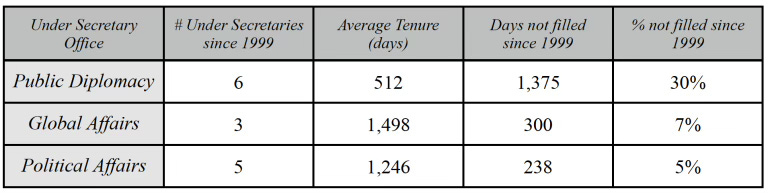

When offices matter, they get filled and they get supported. A December 2011 report by the Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy that my staff and I, as the executive director of that commission, authored compared the gaps between confirmed undersecretaries for the public diplomacy office, the Under Secretary for Global Affairs (now the Under Secretary for Civilian Security, Democracy, and Human Rights), and the Under Secretary for Political Affairs. Differences in the turnover, vacancy, and tenure of the three undersecretaries for the dozen years the public diplomacy office existed to that point is revealing.

Turnover happens, but there are telltale signs when something isn’t right. As Holbrooke noted, there can be a mismatch between requirements and the selection criteria and a lack of support from above and from adjacent offices, neither of which will be magically fixed by a new organization. Undoubtedly, qualified people were identified and approached for the job, and just as likely, these candidates stipulated sensible requirements of support, access, engagement, and responsibilities that did not comport with ossified views of “how things are done.”

Secretary of State Dean Acheson captured the dysfunction, as it should be labeled, of the State Department, which John Foster Dulles amplified when he took the office under Eisenhower and successfully reduced and excised the information function from the department into USIA. Speaking of the department’s information role, assigned to it in August 1945, and its intelligence role, a natural function of the department before the war and returned to the department after, Acheson had this to say:

The Department muffed both of these opportunities. The latter, research and intelligence, died almost at once as the result of gross stupidity… [in 1947] the State Department had abdicated not only leadership in this field but any serious position. Information and public affairs had a better chance and were well served by several devoted assistant secretaries. Eventually. they succumbed to the fate of so many oeprating agencies with which the State Department has had a go, including economic warfare, lend-lease, foreign aid, and technical assistance.

In all these cases, either the Department was not imaginative enough to see its opportunitity or administratively competent enough to seize it, or the effort became entangled in red tape and stifled by bureaucratic elphantiasis, or conflict with enemies in Congress absorbed all the Department’s energed. Then, in the stock market phrase, the new function was “spun off” to live a sort of bloodless life of administration without policy, like the French bureucracy between Bonaparte and de Gaulle.10

It is easier to do nothing. In the case of setting aside hiring this undersecretary, though a career Foreign Service Officer (FSO) is nearly always tapped to serve as the acting official, an FSO has never been nominated or confirmed to the position, reflecting the diminished view of the career within the department and the requirements of the office. But, as Artamonova noted, FSOs did serve as USIA Directors.

The trajectory of Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs is a story of the low regard successive presidents and secretaries of state held for the informational side of policy. It’s also a tale of overlapping efforts, often redundant and increasingly substitutive.

Inconvenient truths

Anyone who continues to think that interest in the informational side policy diminished because the US Information Agency disappeared must confront inconvenient truths: why USIA existed, why AMWG was created, and why was USIA broken up.11 First, as noted above, USIA existed because the Secretary of State, with the President’s permission, rejected that informational policy—including preemptively and reactively addressing disinformation, misinformation, and gaps of information—was fundamental to US foreign policy, not just national security. In 1945, before the USS Missouri sailed into Tokyo Bay, the Secretary of State and the State Department, with the President’s concurrence, agreed that “Modern international relations lie between peoples, not merely governments” and that “International information activities are integral to the conduct of foreign policy.”12 This idea was ultimately rejected in practice and form, and this marginalization continues today and is found in the Commission on the National Defense Strategy’s framing.

Despite decades of evidence that creating USIA was a mistake, based on the authorities it was never granted, there is no evidence that I am aware of that suggests the reintegration of USIA’s non-broadcast functions into the State Department were viewed as an optimization to recenter information in foreign policy. On the contrary, the perceived cost-savings was a major factor: why continue this Cold-War function? This ignorant and short-sighted view came from the same place that militarized our foreign policy and marginalized information from policy and national security. We want to believe the information function merely reacted to the Cold War, but we realized its importance before we realized there was a cold war. This thinking is wrong, illogical, nonsensical, and a defect readily exploited by adversaries.

“What would you do?”

My answer to what I would do rests first on restating the question as the original framing was invalid. The first step toward a solution is not a new organization but establishing leadership. Such leadership must start in the Oval Office and must it be persistent. When invoking USIA, I bet most people will think of the tenure of Charles Wick, or secondarily the appointment of Edward R. Murrow. Both reflect Presidential support. On the latter, Murrow complained about USIA’s limited integration and short-sightedness of US foreign policy when he said he should be in on the take-offs, not just the crash landings. Another complaint, just as applicable today, is that favored method of hurling electrons thousands of miles is the easy part, directly engaging people on the ground is hard, expensive, and most impactful. On the former, I don’t think analysts realize that Wick was not just close to the President, but Wick had the support and expectation to act, something the undersecretaries, save perhaps one, lacked.

The buck stops and starts with the President. But it must flow downward and, like a river, it must be continuous. This means cabinet secretaries, especially but not only the Secretary of State, understand the necessary integration of information and policy and to lead their organizations accordingly. Think of the integration as the military thinks of combined arms, of bringing together different elements of combat power in a complementary and reinforcing manner. Expanding beyond combat power provides a greater appreciation, whether in war or something short of all-out-war.

It is necessary to remember, in the first place, that this war is not one that is being fought by the military forces alone. There are economic, psychologic, social, political and even literary forces engaged, and it is necessary for us in order to defeat the enemy, to understand fully the strength of each. Nor can the investigation stop with the forces of the enemy: it must extend to each country in the world and to every people. The question of winning the war is far too complicated and far too delicate to be answered by a study of only the powers and resources of the nations in arms.13

We consistently fail to appreciate the informational side while adversaries rationally embrace it. The militarization of foreign policy means we are less adept and capable of responding to non-military threats beyond economic warfare. Call this political warfare or something else; these activities easily bypass the Maginot Line military deterrence we’ve built and rely upon. We can complain, but the “information” method is cheap and deniable and supports multiple, even contradictory, attacks. Victory doesn’t mean rebuilding factories or occupying forces, and it can be more enduring. And we let them. They don’t need to try hard to deny these activities since our meager punishments over decades are clearly ineffective and not dissuasive.

Reports calling for “rebuilding” some capacity purport to come from a deep dive or from deep experience, but they don’t, or at least the final product doesn’t show it. These reports inflict on their readers tropes, assumptions, and inaccurate history aimed at symptoms but not the underlying problems. They rarely question what came before and whether they were effective or not. Invoking USIA and AMWG in the same breath is one example. Another example is ignoring the many reports that appeared seemingly every two years from 1961 through the late 1970s arguing that USIA is inadequate and must be reintegrated with foreign policy.

We should not take the tactical route to “rebuild the kind of ability provided by the U.S. Information Agency and the Active Measures Working Group” and paper over exploited defects we must fix. We need the leadership that enables, encourages, and supports the prioritization and integration of the informational side of policy. We cannot stop being reactive without this change. Our adversaries appreciate and center information knowing we are conceptually and organizationally handicapped by leadership that is uncomfortable in this area. We can pretend it’s new, but that’s false and irrelevant. Until the President understands and directs his subordinates accordingly, we will continue to fail to defend against, dissuade, or effectively utilize the informational elements of policy. As a result, we will continue to be outcommunicated because of our decisions, not theirs.

John Foster Dulles happily broke up the predecessor to USIA, the International Information Administration. Formed in 1952 by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, IIA was a semi-autonomous unit within the State Department to streamline the management, budgeting, integration, and accountability of the government’s overseas information and engagement programs within the department and across the government. IIA’s size was considerable, comprising half of the department’s personnel and over 40% of its budget. IIA chaired an interagency coordinating committee that included the State Department, CIA, the Defense Department, and the Mutual Security Agency (overseeing military and economic aid to Europe), positioning it to help an increasingly complex government with mutually supporting words and deeds. The IIA Administrator reported directly to a Secretary of State and managed a portfolio far broader than USIA’s and had direct lines of authority across the State Department and into the field. IIA also owned the State’s department’s relevant relationships with interagency partners and operated with a broader interpretation of “information” than today’s generally narrow concept of words and pictures. USIA never had the responsibilities and authorities it was intended to have. “Buyer’s remorse” emerged within four years, with reports appearing nearly every two years recommending that if needed changes (which largely aligned with the original but never implemented design) weren’t made, the agency should be reintegrated into the State Department. The confusing term “public diplomacy” was adopted in the 1960s as part of the agency’s fight for survival. The modern interpretation of the Smith-Mundt Act as an anti-domestic propaganda law, rather than its actual function as an anti-disinformation and anti-misinformation enabler, stems directly from Senator Fulbright’s attacks on and attempts to shutter USIA (and Radio Free Europe). Fulbright had hoped USIA would close within a few years of its creation. Dulles, for his part, had, before becoming Secretary of State, made clear in 1945 his support for a cabinet-level Department of Peace (a sister of sorts to the still-named Department of War) similar to what IIA became.

It is inaccurate to say the structure of USIA adhered to contemporaneous recommendations. The Rockefeller Committee on Government Organization recommended creating an organization that looked a lot like IIA, not USIA. The Jackson Committee also called for an organization that looked like an elevated but not substantially revised IIA, not fragmented agency with a fraction of the programs and authorities that became USIA. The then-influential and relevant Advisory Commission on Information, today known as the Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy, reversed its support for keeping the programs within the State Department if the replacement was a Cabinet-level agency, a position that would compensate for inaction and the lack of consistent leadership from the State Department and the White House.

That the undersecretary’s portfolio was smaller than the USIA Director’s followed a trend since the USIA Director’s portfolio was also smaller than the position and organization USIA replaced. Relatedly, the USIA Director had a direct line to public affairs operations in the field, whereas the undersecretary had a dotted line, at best, to these offices. The undersecretary had—which likely remains true today—little to no say in who the chief public diplomacy officers are at the nation’s embassies and consulates abroad. Around 2010, the undersecretary argued for and earned “consultative hiring” authority to have a say in who was hired as the public affairs officer at about a dozen or so posts abroad. The subsequent undersecretary squandered this limited authority, and the next undersecretary wasn’t even aware of it. This consultative hiring authority followed the rise of the Arab Spring. The undersecretary wanted to replace a key public affairs officer in a pivotal North African country and was blocked because other elements in the department felt “it would look bad for the to-be outgoing PAO.” Even keeping the PAO in place and assigning an appropriately skilled PAO was blocked since that, too, would “look bad” for the current PAO.

Establishing the Broadcasting Board of Governors as an independent agency did not diminish the authority of the undersecretary relative to their predecessor. The since-renamed US Agency for Global Media’s networks perform a crucial role in combating disinformation, correcting misinformation, and providing information to specific foreign audiences that lack access to accurate and truthful news. It is a vast operation, but not a global one by design (intent and statute). One BBG CEO mistakenly claimed the agency was the nation’s “bulwark” (his word) against foreign disinformation. The State Department always had access to the agency and its networks, and its failure to utilize this access is a related example of failed leadership enabled by higher leadership.

I assume (or hope) there was at least some discussion about the undersecretary beyond the position’s existence during the analysis phase and the report’s production.

Since October 1, 1999, and through August 27, 2024, the office has been vacant 43.8% of the time if we count only officeholders confirmed by the Senate to the position. Setting aside the Clinton administration, when the office was established during the Bush administration, it was vacant 37.2% of the time. During the Obama administration, it was vacant 21.8% of the time. It was vacant 93.2% of the time during the Trump administration term. It has been vacant 68.4% of the time during the Biden administration (and it’s filled by an acting official now). The median tenure is 465 days ( about 15 months), and the median gap between incumbents is 258 days (about 8.5 months). If you prefer averages, it’s 507 days (less than 17 months) and 338 days (about 11 months), respectively. I began tracking this vacancy in 2011 as the executive director of the US Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy. We issued a report in December 2011. See my January 2012 post on that here: https://mountainrunner.us/2012/01/whither_r-2/

For more than a dozen years, I’ve heard from many (and I agree with this consensus) there was one exception to the pattern: Jim Glassman. His term was short, but not only did he come into the position with experience in international affairs, information flows, plus some government experience, he was able to get things done, which attracted collaborative efforts.

In 2011, the head of IIP told me he wouldn’t speak with the assistant secretary of state for public affairs because of concerns the PA sought to take over IIP. I followed up with the assistant secretary on this, and, besides a laughing, said, “is that why he doesn’t return my calls?” A few years ago, IIP was broken up, with most of it going to the Bureau of Public Affairs, renamed the Bureau of Global Public Affairs. Old public diplomacy hands told me they felt a more appropriate name was the Bureau of Greater Public Affairs to reflect, they argued, the greater emphasis on traditional domestic-focuses PA rather than shifting PA toward a global posture. Along those same lines, when I started working on correcting the erroneous and harmful take on the Smith-Mundt Act, serving public diplomacy officers and former USIA officers, more of the latter than the former, tried to dissuade me from that line of work. One yelled at me that I would destroy US public diplomacy because the department was only interested in speaking to the American public. The myth of the firewall nature of the Smith-Mundt Act can be traced to USIA alumni promulgating it to insulate PD activities from domestic PA activities. Every example here is an example of failed leadership, from presidents to secretaries to undersecretaries.

Providing statutory authority for GEC was driven by an interest in expanding its scope to include Russia and to protect it from potential elimination by a possible and then incoming Trump administration. However, the GEC authorization was entangled with a contentious issue: abolishing the board of the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG). The board served as the primary firewall preventing the politicization of the agency’s broadcast operations. Eliminating the board meant the singular head of the agency, the Chief Executive Officer, became a political appointee nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. A key supporter of this political CEO told me it would be just like the USIA Director, which was, in his view, an apolitical appointment. This take was naive and false. In the House, the GEC bill was sponsored by the Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee (HASC), whereas the BBG bill was sponsored by the Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee (HFAC). Both bills were amendments to the pending National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). The HASC Chair threatened to block the BBG amendment. In response, the HFAC Chair threatened to block the GEC amendment because such an amendment was the domain of HFAC. The HASC Chair conceded and allowed the BBG amendment into the House version of the NDAA, expecting the amendment would disappear in the Senate version. However, several senior leaders intentionally misled the Senate while actively withholding information from most of the BBG Governors, including me.

See, for example, Chris Paul’s Whither Strategic Communication? (2009).

Acheson, D. (1969). Present at the creation: my years in the State Department (1st ed.). Norton, p127.

The decision to shutter the agency was finalized in 1997.

MacMahon, A. (1945). Memorandum on the Postwar International Information Program of the United States (July 5, 1945). US Government Printing Office. An abbreviated December 1945 edition is more known (the latter did not include chapters that had been overcome by events: advice for dealing with Congress regarding 1945-1946 fiscal year-end issues and budget and organizational issues related to the war continuing into 1946). The Office of War Information (OWI) used this report and this text in its recommendations to Truman, per the President’s request, on the disposition of OWI’s functions after the war. Those recommendations were adopted by Truman and used in his August 31, 1945, executive order that transferred the international information activities of OWI and the Office of Inter-American Affairs (OIAA) to the State Department.

I’ll give you the reference, but I’m not sure you’ll believe it. The year is not a typographical error. Military Intelligence Division of the US Army General Staff. (1918). The Functions of the Military Intelligence Division, General Staff. Military Intelligence Division, General Staff.

Another Illuminating post! Lately I’ve wondered whether wargaming could be used to analyze narrative warfare matters. Efforts are lacking in trying to develop methods and scenarios for gaming story-wars.

I see that a Robert Domaingue, right after retiring from the U.S. State Department, where he’d been the lead Conflict Game Designer in the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations, called on State to create its own Office of Diplomatic Gaming, in article titled article on “Why the State Department Needs an Office of Diplomatic Gaming” (2022). It verges on calling for story-war gaming.

I’ve also found that the UK’s Ministry of Defense (MOD) has issued an Influence Wargaming Handbook (2023) — the first of its kind. The handbook claims that “wargaming is particularly suited to exploring and representing influence” (p. vi) — but it is sensibly cautious about the conceptual and methodological challenges that lie ahead for wargaming influence.

Wargaming might be a good path to go down in order to call for improved attention to information etc. matters that keep being neglected.

Great points as ever — so frustrating that the R post is reduced to an acting undersecretary once again. Imagine if the Navy was treated this way…