The Fulbright Paradox: How the "Relic of the Second Zulu War" Continues to Undermine National Security, Part I

The first of an occasional series

A striking mythology surrounds Senator J. William Fulbright as a patron saint for US public diplomacy. It is found in many biographies – with some works arguably worthy of the label hagiography – and countless descriptions of US exchange programs. It is a narrative that is not just selective, it is built on inaccuracies and flagrant omissions. Understanding Fulbright’s true relationship with US public diplomacy reveals his actual lasting legacy: the kneecapping of US global engagement.

This is the first of an occasional series of posts that takes aim at the mythology of Fulbright’s contribution to US public diplomacy. The specific focus of this post is how Fulbright’s deliberate acts continue to have a deleterious effect on how we conceive, organize, and conduct international information programs.

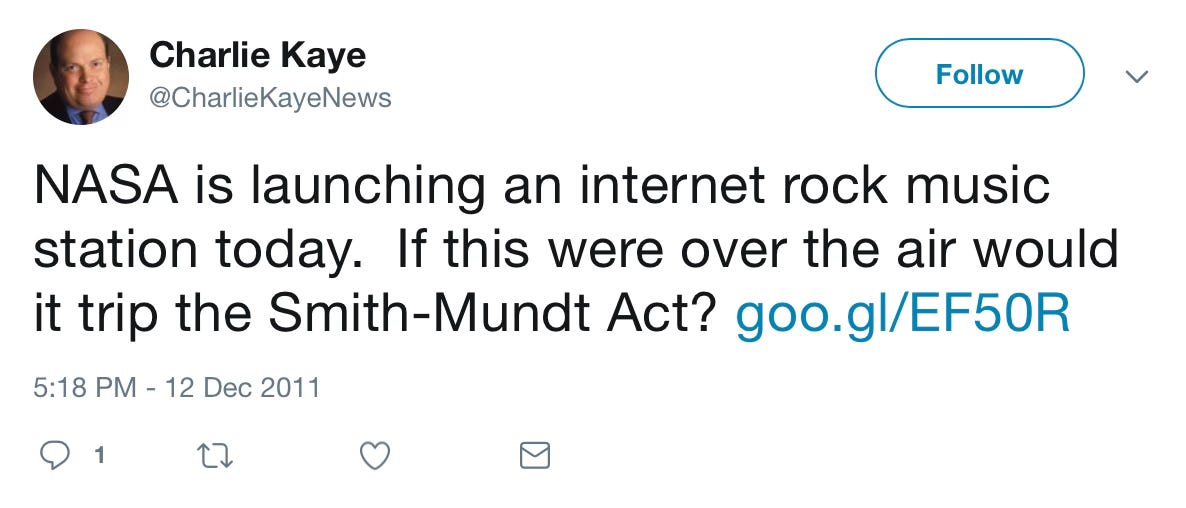

It is profoundly ironic that scholarly and legal analyses, not to mention policy discussions, about confronting disinformation and misinformation are often filled with and rely on misinformation. Exposing this history often feels like tilting at windmills. But as a budding historian on the subject, the devils that lay in the detail reveal a trajectory at significant variance with the accepted narrative. Around the topic of the Smith-Mundt Act, discussions are remarkably deficient and often start with a post-Fulbright narrative and then work backward. The result is Fulbright’s intentions are filtered, laundered, ignored, or, more often, simply unrealized. A product of this distorted history can be found in a Gates Center report from 2022:

Yet, legislative restrictions inhibit America’s ability to cultivate a strong domestic constituency to advance U.S. reputational security. A 1972 revision to the Smith-Mundt Act (with the good intention of protecting the American people from being propagandized by their own government) separated foreign and domestic strategic communications, but with the unintended consequence of hurting the ability of the agencies tasked with these activities from engaging with the U.S. public to build their awareness, leverage their capabilities, or ensure that the government’s efforts are transparent and accountable.1

This paragraph tells us that Fulbright’s 1972 “revision” came from a “good intention,” but it didn’t. The accepted history here is wrong, reinforced by faulty arguments in law review articles like “Apple Pie Propaganda?” by Weston Sager and “The Smith-Mundt Act’s Ban on Domestic Propaganda” by Allen Palmer and Edward Carter.2 The “unintended consequences” were, in fact, Fulbright’s intended consequences. Reading this, it is difficult to imagine the scope of the “revision” was limited to the US Information Agency. Except it was. The USIA and its Voice of America operated under the authority of the Smith-Mundt Act. Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty (merged five years later into RFE/RL) were not established by the Smith-Mundt Act, nor did they fall under the Smith-Mundt Act’s purview, and thus were not affected at the time by the amendment. The same lack of applicability was true of the White House, the State Department, the Defense Department, or any other government agency. And yet, we are led to believe from the parenthetical and virtually every other reference to the Act in this context, including notably seemingly every law review article looking at the Smith-Mundt Act, that the application and intent was the whole of government. These analyses fail to distinguish between the vast information programs enabled by the Act (including increasing funding for public affairs officers in the field to do what they do) from the broadcast radio operation (Voice of America). It doesn’t take a close read to realize the law review articles focus on the radio operations rather than on the former, which were vastly more extensive in terms of dollars, audience, scope, and personnel.3

The roots of his 1972 “revision” to the Act were on stark display in a Senate hearing five years earlier, but the seeds were evident in 1953 with his influence on what did and did not move from the State Department to USIA. However, his efforts to undermine international information engagement were not limited to USIA or Smith-Mundt and included killing an effort that enjoyed bipartisan support and broad public awareness and support to better defend the nation and its interests against foreign political warfare.4

The amendment resulted from Fulbright’s argument that simply allowing the US public to see what USIA produced for foreign audiences would make the agency an arbiter of truth and worse. To better grasp Fulbright’s position, see the dialogue snippet below from a 1967 hearing between Fulbright and Dr. Frank Stanton, the chairman of the US Advisory Commission on Information, the president of CBS, and, until a week before this hearing, also the chairman of the RAND Corporation.5

Chairman Fulbright: You, I think, are saying that all of our foreign propaganda is the truth, and I think this is very questionable. The truth is that most Government propaganda diverges from the truth…

Dr. Frank Stanton6: Is there not a better chance or a better opportunity, Mr. Chairman, if the press, the public, and the Congress can look over the shoulders and check what is being said? Is there not a better opportunity to make sure that we do not indulge in anything other than the truth as we see it?

Fulbright: It has been the common practice throughout history for governments to distort the truth for their own purposes, just as I think was done in the Defense Department film. Personally, I think the account, historically speaking, given by General Westmoreland before the Associated Press in New York yesterday had some grave inaccuracies in it. I do not think it is true that this is not a civil war. I think it is a civil war, and all the scholarly authorities in this field outside of the Government so state. There certainly is a difference of opinion. But here you have a recent example. Since CBS carried it, does that mean you thought it was the truth?

Stanton: No, I think when a responsible officer of Government or the military makes a statement, we cover it as news. We do not say that because we carry it, it is necessarily true.

Fulbright: Just because the USIA carries it does not make it necessarily true either, does it?

Stanton: No, but I did not think that was necessarily the issue here. I think there is a better chance of making sure that they tell the truth if the people here can judge it.

Fulbright: What people here? You mean the public generally?

Stanton: Yes.

…

Fulbright: It seems to me if the USIA tells the truth, as you seem to believe, then the U.S. public can know what the USIA is saying through the established media, through CBS, the Baltimore Sun, and the New York Times. Are they not truthful?

Stanton: I would be the last to say that they were not, but that is not the point of the exercise. It is to let the people see what our Government is saying to the rest of the world. It is not a question of testing the truth in each instance.

Fulbright: Then it is important to know what the USIA is saying by checking on whether they are telling the truth or not.

Stanton: That would be one of the by-products of the exercise [of clarifying “on request” to allow greater domestic access to USIA materials].

Fulbright: I think that is the reason it is made available to Members of Congress or members of the press. The members of the press can go to USIA and check the truth of the information. But to make it publicly available, I think, is turning it into propaganda. If a Communist country did it, we would call it brainwashing.7

Stanton: Only if the Government or only the agency active distributed the material. That is the distinction that would make.8

There is a crucial point of distinction that Fulbright refused to entertain and law review articles and the like ignore: the difference between accessibility and distribution. Stanton said before the above exchange: “It is not our suggestion that USIA product be made available to tell us about us, but that we may know what our government is telling others.”

Barring domestic oversight and awareness and policing domestic access to the content was, Stanton pointed out in his dual-hatted role of oversight and advocacy, problematic:

We are saying to the people in Indonesia or in Africa, “What you are hearing about the United States, the people in the United States are not allowed to hear about. We are telling you one thing, but the people in the States are not privy to this information.” If we are going to be persuasive, that our freedom means something to the people in the developing countries, and for that matter all over the world, I see no reason why we cannot let the people here see what we are saying outside the United States.

It should be clear by now that Fulbright’s position was based on distrust and dislike of the executive branch’s public statements. He responded by attacking and trying to shutter or muzzle what he could. In 1972, the amendment was just one prong of a broader effort by Fulbright to eliminate funding for Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty and starve VOA while strangling USIA.9 Fulbright’s attempt to slash funding for these operations is a forgotten failure. However, his other line of attack, revising the Smith-Mundt Act’s provision that intentionally provided for transparency and oversight to erect significant barriers to both, was a success.

His broad brush strokes were not just because he didn’t want the US public to know what USIA and VOA sent abroad or that RFE requests for public donations should note funding also came from the US government. He felt these operations were inherently wrong. In 1953, he successfully argued to keep the exchange programs from moving from the State Department to the new USIA to avoid the taint of the information programs.

While seemingly a minor correction to the Smith-Mundt Act at the time, its harmful effects continue to be felt today. In another post, I’ll discuss Sen. Zorinsky’s 1985 amendment to the Smith-Mundt Act to close the “loophole” in Fulbright’s amendment, a change that led a federal court to rule USIA materials were exempt from Freedom of Information Act requests. I doubt Fulbright would have imagined the extent of the damage done by his 1972 amendment to the Smith-Mundt Act, but I am wholly confident he would be pleased.

The 1972 revision, furthered by the 1985 amendment, led to the “firewall” concept that was played up by USIA alumni after 1999 when most of USIA’s information operations returned to the State Department. The effort to maintain a separation between domestic and foreign engagement at the State Department was also evident in the title of the notional successor to the USIA Director, the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs.10

But what happens now that the State Department’s Bureau of International Information Programs, formerly the most significant yet ignored artifact of the former USIA, has returned to its original home of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs, renamed the Assistant Secretary for Global Public Affairs? I don’t know, but we have something of a full circle. The Assistant Secretary for Public and Cultural Affairs, established in December 1944, was “to develop a program designed to provide American citizens with more information concerning their country’s foreign policy and to promote closer understanding with the peoples of foreign countries.” This meant this position owned both the domestic and foreign information and exchange portfolio until 1952.11 Today, instead of quality-based challenges resulting from oversight and awareness, we have the blanket Fulbrightian-based “anti-propaganda” narrative that denies awareness of intent, content, and value. This is fundamentally against the original and clear intent of the Smith-Mundt Act.

You’ve read this far, so you’re probably wondering about the title of this note. The Fulbright paradox is not just about his elitism, one expression of which was that “he considered democracy in many ways a dangerous experiment,” with another was his focus on elite university-level scholars.12 Or his atrocious civil rights record.13

The paradox is his antipathy to public diplomacy organizations and operations, outside of exchanges (or rather, exchanges as long as they didn’t have the Mundt name on them). During a budget hearing in 1971, Fulbright opined that “Radio Free Europe has done more to keep alive the cold war and prevent agreement with Russia and improved relations than good.” In 1972, on his way to passing the “revision” the Gates Center report recalled, Fulbright declared Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, and Radio Liberty should be “given the opportunity to take their rightful place in the graveyard of Cold War relics.”14

In 1973, Fulbright’s “political cliches” and “semantic blackmail” levied against the USIA, VOA, RFE, and RL over the prior decade led a witness in a Senate hearing to ponder why Fulbright wasn’t referred to as a “relic of the Second Zulu War.”

The Smith-Mundt Act was developed and designed to counter foreign disinformation, correct foreign misinformation, and fill in the gaps in the absence of information abroad about the US, its policies, and the society behind those policies to help audiences understand the nation’s intentions. It was also, it’s worth noting, to help promote the then-new United Nations as a means for international peace, though much of that language was removed before the final signing. Despite reality, and the clear text and purpose of the Smith-Mundt Modernization Act of 2012,15 there remains the irony of continuing misinformation around the legislation, its function, and the intentions of the original act and those who amended it.

This missive should provide some background for what will be an occasional series highlighting how Fulbright willfully hampered the nation’s non-military means of engaging with the world. Put another way, he helped militarize US foreign policy by denigrating, handicapping, and relegating non-military methods that were critical then and remain, if not more so, today.

The lament below, from 1963, followed an earlier, and totally forgotten, act of Fulbright’s against a similar effort to deal with foreign disinformation and subversion, and unrelated to USIA. The quote remains relevant today, just as it remains true that Fulbright is arguably the central cause of why we lack a solid comprehension of the tools, policies, support, and oversight we require today.

“Someday this nation will recognize that global non-military conflict must be pursued with the same intensity and preparation as global military conflicts”

[Ed: see the follow-ups to this post, one in text and the other a read-through with commentary of the former.]

Custer, Samantha. Reputational Security: The Imperative to Reinvest in America’s Strategic Communications Capabilities. Williamsburg, VA: AidData at William & Mary, 2022, p18. Download: https://www.aiddata.org/publications/reputational-security-the-imperative-to-reinvest-in-americas-strategic-communications-capabilities.

Sager, W. R. (2015). Apple Pie Propaganda? The Smith-Mundt Act Before and After the Repeal of the Domestic Dissemination Ban. Northwestern University Law Review, 109, 511-546. Palmer, A. W., & Carter, E. L. (2006). The Smith-Mundt Act’s Ban on Domestic Propaganda: An Analysis of the Cold War Statute Limiting Access to Public Diplomacy. Communication Law and Policy, 11(1), 1.

Interestingly, Palmer and Carter eventually arrive at a recommendation that aligns with the original intent of Congress, the State Department, and the press when the Smith-Mundt Act was debated and signed into law: “But, if taxpayers who fund the production of international propaganda desire to view the materials for themselves and initiate a request under the Freedom of Information Act, the government should not be allowed to keep the materials shrouded in secrecy.” On the other hand, while better at recalling history, Sager still misses critical details that undermine the “Apple Pie Propaganda” narrative. However, “for dissemination abroad” was an explicit blanket authority requested by the State Department, not a restriction imposed by Congress. That the “on request” language was a mutually agreed upon budgetary and practical barrier not intended to prohibit domestic access. The concern was Members of Congress and the press would make blanket requests for materials that would never be read but would require more funding for the department for additional translators, typists, filing capacity, etc. The non-compete clause in the Act is inadequately considered in its domestic intent and effect on foreign operations. Further, the law review articles fail to distinguish between types of content as they often conflate source agencies while failing to distinguish between broad information programs and broadcast operations, instead relying on vague implications. There are other points, but this is a footnote.

Even as late as September 1947, the State Department’s objective was still to move the radio operations – Voice of America – out of the government. In a list of the State Department’s pending legislation near the end of the first session of the 80th Congress supported, number 3 was a bill to move the radio into a not-for-profit funded by the government. The top two bills were “Entry of Displaced Persons” and the World Health Organization, with the pending Smith-Mundt bill nowhere on the list. It was co-sponsor Smith, by the way, who primarily blocked the privatization of VOA. Sen. Smith didn’t like the idea of a government function he considered important to be run outside of government and away from foreign policy. Removing the path toward privatization appeared to be a condition of his cosponsorship in the Senate. From the State Department and the House’s point of view, the radio operation – the news business directly in competition with the private sector – was the primary lightning rod and complicator, as was identified in the July 1945 report mentioned earlier. The best solution was to move the operation, which clearly was to augment and not supplant private media, away from the government. (Thought exercise: if Voice of America had been privatized in 1947 or 1948, would RFE still have been formed in 1949, RL in 1951, and Radio Free Asia in 1952? Or would they have taken a different form?)

The Smith-Mundt Act established the US Advisory Commission on Information to provide expert, timely, and relevant advice to Congress, the Secretary of State, and the White House. The commission was subsequently merged with its sister commission focused on exchanges to become the US Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy. It requires a considerable stretch of the imagination to consider today’s commission relevant or capable of engaging in an even remotely similar discussion.

Stanton was then the chairman of the US Advisory Commission on Information. He was also the president of CBS and, until a week before the 1967 hearing this exchange is from, had been the chairman of the RAND Corporation. It requires imagination to pretend today’s commission might be viewed as relevant or capable in such a discussion today. I’m hard-pressed to imagine a commission member participating in a similar debate today. Further, I’m not aware that any of the present members of this commission have ever been asked for their input in a Congressional hearing.

“Brainwashing” here was Fulbright referring to the article “On the Way to 1984” by Henry Steele Commager, professor of history at Amherst College, published on April 15, 1967, in the weekly magazine Saturday Review. Commager opening included this line, which Fulbright clearly agreed with: “Now the information agencies of our own State and Defense Departments, the USIA, and the CIA, seem bent on creating an American Ministry of Truth and imposing upon the American people record of the past which they themselves write.”

Before the above exchange, Fulbright asks Stanton about Radio Free Europe. Fulbright took umbrage with the public line that RFE “was supported by private funds, send your contribution.” Fulbright objected that public solicitations did not say funding was “in part” by public donations, as in it also received government funding. “Do you know who really supports Radio Free Europe?” asked Fulbright. Stanton replied, “I believe it is one of the best-kept open secrets that we have.”

Fulbright's 25% cut to USIA’s budget was intended to fall heaviest on VOA. USIA anticipated reducing VOA’s language services from 35 to just 11. This reminds me of three conversations I participated in as a Governor on the Broadcasting Board of Governors. First was the salon dinner (8 people) at a DC-area home where Alec Ross, sitting next to me, argued the BBG should shrink to three or four languages and “surge” into other languages when necessary. Second, there was a meeting with the Office of Management and Budget about the BBG’s budget. The OMB suggested BBG start taking advertising sponsors to reduce the federal appropriation by as much as 50%. Another shocking display of ignorance of the BBG’s audiences and environments (i.e., generally not open to safe commercial trade, must build and maintain trust), not to mention the inevitable influence sponsors would have on content. The audience and environment issues seemed to have a lesser effect on the OMB than learning there would need to be a new internal bureaucracy at BBG to manage the advertiser/sponsor relationships. Third was an argument by a colleague at my level who felt BBG’s news operations were mere translators and could be shuttered, with the broadcast ops simply would forwarding NBC, CBS, Fox, CNN, etc, abroad.

Adopting the term “public diplomacy” in 1965 is a different story. See my chapter for a discussion on this: https://books.google.ch/books?id=kuYJEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT110#v=onepage&q&f=false

The office was established in December 1944 with Archibald MacLeish as the inaugural incumbent. William Benton, MacLeish’s successor, removed culture from the title because it was, he said, a lightning rod. The Assistant Secretary had this broad portfolio until 1952 when it was turned over to the Administrator of the newly established International Information Administration, a semi-autonomous unit in State. Technically, USIA came from ripping much of IIA from State rather than from the Assistant Secretary’s portfolio.

With the expanded Assistant Secretary for Global Public Affairs, I’m still wondering what the unique role of the notionally superior Under Secretary for Public Diplomacy is. Let’s not forget this under secretary has not had a confirmed incumbent for nearly half of the past two dozen years. See https://mountainrunner.substack.com/p/r-changes-coming.

There is an interesting division between those involved in education that supported the information programs. Those who sought to engage students and teachers at elementary school and above supported the information programs (Rockefeller, Mundt, Benton). Those who opposed were focused only on university-level education (Cherrington, Fulbright).

Here’s how Fulbright biographer Randall Bennett Woods described Fulbright: “That J. William Fulbright was a racist is indisputable. He would claim throughout his career that his position on civil rights was a matter of political expediency… To his mind the blacks he knew were not equal to whites nor could they be made so by legislative decree.” But then Woods follows up: “On a personal level he judged people by their manners, personal cleanliness, and education, not by their skin color; but he did not feel compelled by Christian duty or social conscience to use the power of the state to remedy historical wrongs, correct maldistribution of wealth, or legislation equality of opportunity.” Woods, R. B. (1995). Fulbright: a Biography. Cambridge University Press, p115. In January 2009, I was on a panel of public diplomacy luminaries and had the chance to meet Harriet Fulbright, the wife of the late Senator. After the panel, I asked her about his views on race. “He had his faults,” she said. The quote about democracy is found on p110 of Woods's biography.

Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Senate Committee on Government Operations. (1973). Negotiation and statecraft hearings, Ninety-third Congress, first session. Pursuant to section 4, Senate resolution 46, 93d Congress. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off, p66. For Fulbright’s statement, see Gwertzman, B. (1972, February 21) “Funding Near End for U.S. Stations Aimed at Red Bloc.” The New York Times, pA1. The whole sentence was, “These radios should be given an opportunity to take their rightful place in the graveyard of cold war relics.” (Cold war is indeed lowercase in the original.)

It continues to boggle my mind that Defense Department folks still cite the Smith-Mundt Act as blocking this, that, or the other of their planned or desired activities when the Modernization Act’s cause, purpose, and clear language affirms this Act has nothing to do with the Defense Department. Does anyone read this stuff?

Looking forward to a summary of how we might change the law and who might champion PD on Capitol Hill.

As a “budding historian on subject” – his self-designation – Matt makes many sweeping, dramatic, and revisionist claims about the history of public diplomacy and about Senator Fulbright, and he wants to unmask Fulbright as politician, who has been responsible for undermining national security since 1953 – or at least 1972. His task in the future will be to document how Fulbright “continues to undermine national security.”

Frankly, I am personally perplexed by Armstrong’s claim that the “actual lasting legacy” of Senator Fulbright is “the kneecapping of U.S. global engagement.” This appears to be based on Matt’s assumption that the scholarly and legal analysis of the Smith-Mundt Act to date is more or less flawed across the board; that the “accepted history” is “wrong”; that the implications of Fulbright’s 1972 amendment were epoch-making; and that they have had a negative and lasting effect for the past fifty years.

I want to preface a few observations by noting that I find many of Matt’s previous posts more convincing. For example, in his “R Changes Coming?” post on his Substack from January 30, 2023, he identified a lack of PD leadership, a lack of PD funding, and a lack of Congressional interest in PD since 1999 as problems, and he pointed out that the office of the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs had been vacant almost half of the time since it was established in 1999.

It is not clear to me how Fulbright is related to these shortcomings, but I am not a specialist in public diplomacy or in the history of U.S. public diplomacy like Matt. However, I have done some work on the history of the Fulbright Program, and I would like to suggest that it would be helpful for the readers of Matt’s Substack to have a bit more information to Fulbright’s skepticism regarding governmental information programs. This is a long story that goes back to the “first cold war” in the 1950s.

Stacy Cone has written an informative article on Fulbright’s engagement in the antipropaganda movement – “Pulling the Plug on America’s Propaganda: Sen. J.W. Fulbright’s Leadership of the Antipropaganda Movement, 1943-74,” Journalism History 30, no. 4 (2005): 166–76 – that contextualizes Fulbright well. He “had long been the most proactive propaganda critic in Congress, but he was far from being the only one and further still from being the first.”

Matt uses what he calls a “snippet” of an exchange between Senator Fulbright and Frank Stanton, the Chairman of the U.S. Advisory Commission on Information, from a hearing in 1967 as an example of “Fulbright’s position” instead of citing substantially more important works that contextualize Fulbright’s concerns regarding the manner in which presidential administrations and U.S. government were informing (and misinforming) the U.S. public in the 1960s.

Fulbright documented his reasons for what Matt called Fulbright’s “distrust and dislike of the executive branches public statements” in three books: Old Myths and New Realities and Other Commentaries (1964); The Arrogance of Power (1966), which had the distinction of being a best-seller; and The Pentagon Propaganda Machine (1970) . Fulbright was of the opinion that American anticommunism was misguiding policy in Latin America, Southeast Asia, unnecessarily exacerbating the East-West conflict, and fueling the arms race, thus increasing the risk of a nuclear war, the avoidance of which was consistently his highest political priority.

Matt traces Fulbright’s allegedly malignant influence back to the Senate subcommittee hearings on “overseas information programs” chaired by Fulbright in 1952 and Senator Bourke Hickenlooper (R-Iowa) in 1953: twenty-five days of hearings with over 1,500 pages of testimony on film, broadcasting, press work, libraries, and exchanges. It is worth noting that Alexander Smith (R-New Jersey) and Karl Mundt (R-Iowa) served on this special subcommittee, too.

One of the most important outcomes of these hearings – from the perspective of the integrity of exchange programs – was the consensual Congressional opinion that bilateral cultural and educational exchange programs based on the idea of dialogue – or “mutual understanding” – should be institutionally segregated from policy-driven, unilateral “information programs” – especially film, radio broadcasting, and print media – with their objectives of informing, shaping, influencing, or manipulating foreign public opinion.

This insight was based on the assumption that educational exchange and propaganda/information programs were fundamentally different enterprises and the the organizational segregation of the former from the latter enhanced the credibility and impact of exchanges. Hence, the management of exchanges was “retained” in the State Department’s International Education Service (IES), the forerunner of the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA), when USIA was chartered in 1953 (and only belatedly incorporated into the USIA portfolio after 1978, when the Fulbright Program was rebranded the USIA Fulbright Program).

The 1953 testimony of Walter Johnson, the Chair of the Fulbright Board of Foreign Scholarships, is particularly instructive in this context. Johnson commented on the unique nature of the Board of Foreign Scholarships and its role in the governance of the program, the structure and importance of binational commissions, and the reliance of the program on Smith-Mundt funding. He also argued that “[I]t is most unfortunate that the exchange program and the information program are in the same division of the Department of State. The long-range foreign-policy objectives of international understanding through educational exchange are different psychologically from the short-range objectives of day-today foreign policy persuasion as carried out by the mass media.”

Matt’s task will be to document how the position of Fulbright – and Smith and Mundt in 1953 – can serve as pre-history for Fulbright’s 1972 amendment and then to document how Fulbright’s noxious influence has been a driving force in the “knee-capping of US global engagement” in the course of the fifty years since then.

I am at a bit of a loss to comment on Matt’s aside about Fulbright’s alleged “elitism.” Fulbright’s concern about democracy as a “dangerous experiment” was based on the fragility of democracy, not its principle inadequacies. The focus of the Fulbright Program on graduate students as a primary target group and scholars as a secondary one was based on the insight that the impacts of the exchange experience would be greatest for these academic cohorts (as opposed to primary and secondary school students and teachers) and reinforced by the U.S. government’s initial experience of organizing exchanges with Latin America in the 1940s.

Fulbright’s own Rhodes experience also informed his original conception of the program. As a graduate of a land-grant institution in the South and a Rhodes Scholar, Fulbright was concerned about an equitable national distribution of awards from the very start, and he advanced the idea of a representative national geographical distribution of Fulbright awards from the very start. The mantra of the Fulbright Program from the start has been annual, open, national, merit-based competition.

Matt references Fulbright’s “atrocious record on civil rights” –I have used the term “deplorable” – and cites Randal Woods’ Fulbright’s 1995 biography of Fulbright in a footnote: “That J. William Fulbright was a racist is indisputable.” Woods never convincingly documented this opinion, which was immediately contested by many of Fulbright’s contemporaries, and he toned it down in a Fulbright obituary a few years later with a reference to Fulbright’s patrician upbringing with the qualification that “his racism had much more to do with class than skin color, . . . “

It is important to note in this context that Lee Riley Powell published a fine and lawyerly second full-length biography of Fulbright – J. William Fulbright and His Time – which appeared in 1996 one year after the Woods biography and should be read parallel to Woods’ book. Powell, who critically deals with Fulbright’s civil rights record at great length and contextualizes in Arkansan politics, also takes Woods to task on a number of stylistic and methodological issues by observing, for example, “. . . it is shrill and superficial to not only dismiss Fulbright as a racist, but to claim that his alleged ‘racism’ was ‘indisputable.’”

Finally, the most recent extensive evaluation of Fulbright’s legacies at the University of Arkansas in 2021 came to the conclusion that his voting record against civil rights “reflected the demands of political expediency of the times” that “did not reflect a hardened personal racism toward African Americans” but was “more a reflection of his need to appease a voting constituency that was not ready for social change.”

Three different disparate legacies were part of Fulbright’s public political persona during his lifetime: the international educator, the Southern Democrat, and the dissenter. Stacy Cone would add a fourth legacy: “his postwar leadership of the disorganized, dispersed, but indefeasible antipropaganda movement in America.”

According to Matt’s post, in 1972 Fulbright, the international educator, advocate for disarmament and detente, and tireless advocate for ending the war in Vietnam, “helped militarize US foreign policy by denigrating, handicapping, and relegating non-military methods that were critical then and remain, if not more so, today.” Is this Fulbright’s newest and fifth legacy? The militarist?